365 Dry Martinis

My notes on jazz recordings, served (almost) daily.

Recent listening, current

Archived listening, 2013-2016

Thursday, October 22, 2020

215. George Harrison / Early Takes, Vol. 1 (2012)

I listen to this collection of demos and early takes more often than I do All Things Must Pass. I love Harrison's chords... there are so many good changes. Most takes are just him with a guitar, and sometimes a drum track or overdub. It's an intimatre setting: you can hear his feet on the floor keeping time, or taking breaths between phrases. The simplicity of the demos lets their beauty shine through unobstructed. This is easy music for a hard time... "All things must pass away," as Harrison reminds us. Also: "You don't need a horoscope or a microscope to see the mess you're in." Right? Well, it is 2020. Every bit helps.

Thursday, July 16, 2020

214. Sacred System / Chapter One: Book of Entrance (1996)

Dub alert. Book of "En-trance," get it? I got into Laswell after I saw his credit on albums by people like Henry Threadgill, then discovered his towering discography under many pseudonyms. Laswell works in NYC with everybody from Nona Hendryx to John Zorn. I get the impression that if you hung around the Bowery for long enough, and made a habit of staying up way past your bedtime, you'd eventually end up recording with him. 'Chapter One' is the first of four records (I think it's four) under his Sacred System moniker. The music is a unique flavor of ethereal trance-oriented dub. Tracks build from subtle, soulful bass grooves into all-out psychedelic dub glaciers where the keyboards speak in tongues, replete with weird echoes, prepared loops, backwards banshee wails, and self oscillating delays... but chill, really chill. You get the picture.

If you're not all that into trance or dub, or you get turned off by the genre description, please understand that this is not your garden variety, up-all-night dance soundtrack. Laswell is a master producer and does not employ effects for their novel value, nor does he beat you over the head with them. (He doesn't beat you over the head with his beats, either.) He knows how to build a musical track into an eight-minute experience for the ears and mind; his aural soundscapes are constantly in flux, with new textures coming and going, perking the attention span. It's a process of regeneration -- new chittering spasms of sound are born as others decay, so out with the old and in with the new as the groove rolls onward. The bottom line is that you never know what's lurking around the next sonic corner. 'Book of Entrance' is a fantastic example, not just a clever title.

If you're not all that into trance or dub, or you get turned off by the genre description, please understand that this is not your garden variety, up-all-night dance soundtrack. Laswell is a master producer and does not employ effects for their novel value, nor does he beat you over the head with them. (He doesn't beat you over the head with his beats, either.) He knows how to build a musical track into an eight-minute experience for the ears and mind; his aural soundscapes are constantly in flux, with new textures coming and going, perking the attention span. It's a process of regeneration -- new chittering spasms of sound are born as others decay, so out with the old and in with the new as the groove rolls onward. The bottom line is that you never know what's lurking around the next sonic corner. 'Book of Entrance' is a fantastic example, not just a clever title.

Monday, July 13, 2020

213. Santana / Moonflower (1977)

Moonflower, released 1977, is a mixture of new studio material and contemporary live performances that demonstrate, in equal measure, all components of the Santana sound. Carlos Santana had spent the previous decade exploring the nuanced corners of this thing he’d invented called “Latin jazz rock fusion.” Of course, we didn’t call it that back then, we were still a few decades away from piegonholing everything into an early grave. The unique music was just the thing that Carlos did. But by the time Moonflower reached audiences, he’d come to the top of the pyramid and was ready to jump off. So the form I’m talking about -- a lysergic combination of free-form acid rock punctuated by Latin dance rhythms of primal intensity, and buoyed by the harmonic message of jazz and slick sensibilities of pop -- as far as I am concerned, was perfected right here. All the other Santana records up to this point demonstrate one of these aspects superbly, but only now are they brought together under a single heading. Such a culmination of style is the reason Moonflower is just so damned good, and why you need to stop whatever it is you’re doing, right now, and listen to it for at least a week, straight.

Santana’s guitar is a sustain bomb, famously so, and it comes in spades on this album. We call it, “neverending sustain” because that’s exactly what it is -- a controlled feedback loop between a guitar pickup and a very loud amplifier, and Carlos basically wrote the book on it: First, crank a tube amp to within a few volts of its life. Then, plug in your guitar and roll its volume knob back to a level that won’t cause a lawsuit. As the notes you play start to fade, roll that volume knob back up to keep them going. Once you hit the sweet spot, just stand there and let the message ring…. forever if you want. In this way, a few well placed strokes of the pick become epic vehicles of self expression, whole chapters in the book of whatever your song is trying to say. At least, that’s how it works if you’re Carlos Santana. During soundchecks, he paces around the stage playing the guitar until he finds the magic distance to stand from the amp, and marks off the spot with duct tape. His amplifier cabinets sit at waist level so the speaker can see the guitar. The whole process is calculated and diabolically simple, but the net effect is packed with an intensity that so belies its simplicity, you’d swear it’s witchcraft. The sound is rapturous bliss, or euphoric jubilation. Otherworldly. It’s a miracle note. It shouldn’t still be there, it should have melted away to silence by now, but there it is. And therein is another component of Santana’s music, amply demonstrated on Moonflower -- the magic-realism of Latin folklore, the power of the supernatural in everything, and the tingling, electric sensation of listening to a really good Santana record.

To get the gist of what I’m saying, turn up the stereo good and loud. Do it in the car, in a parking lot, standing still. Don’t try to drive while appreciating guitar feedback to its fullest capacity for fulfillment. Do it in an armchair with a good pair of flat response cans, or, if no one’s home, open the fader and let the sound blast through your speakers. Moonflower offers high grade sonic transcendence on tap. For the experience of a live concert, listen to the careening beauty of “Black Magic Woman,” “Savor,” or “Soul Sacrifice” from the Abraxas era, complete with Carlos’ signature fuzz and effects, and the raucous, chaotic energy of Chepito Areas on percussion. Songs like “Europa” and “Transcendence” softly (but not quietly) offer the quintessential example of the Carlos Santana Sound in its starkly beautiful phrases and lengthy single-note passages of sustained sound. The latter features a masterpiece solo that you don't want to miss. With a snazzy snap and velvet touch, the subtle hooks of newcomers like “I’ll Be Waiting,” “Zulu,” and “Flor d’Luna” point to the coming years when Santana transitioned to pop and album oriented rock. If Caravanserai is the album that bridges the gap between Santana's acid rock genesis and their more advanced forays into further realms of jazz and progressive rock, then Moonflower is likewise the album that marks where Santana funnels all it learned from the second part of the journey, and strikes off in a new direction once again.

Santana’s guitar is a sustain bomb, famously so, and it comes in spades on this album. We call it, “neverending sustain” because that’s exactly what it is -- a controlled feedback loop between a guitar pickup and a very loud amplifier, and Carlos basically wrote the book on it: First, crank a tube amp to within a few volts of its life. Then, plug in your guitar and roll its volume knob back to a level that won’t cause a lawsuit. As the notes you play start to fade, roll that volume knob back up to keep them going. Once you hit the sweet spot, just stand there and let the message ring…. forever if you want. In this way, a few well placed strokes of the pick become epic vehicles of self expression, whole chapters in the book of whatever your song is trying to say. At least, that’s how it works if you’re Carlos Santana. During soundchecks, he paces around the stage playing the guitar until he finds the magic distance to stand from the amp, and marks off the spot with duct tape. His amplifier cabinets sit at waist level so the speaker can see the guitar. The whole process is calculated and diabolically simple, but the net effect is packed with an intensity that so belies its simplicity, you’d swear it’s witchcraft. The sound is rapturous bliss, or euphoric jubilation. Otherworldly. It’s a miracle note. It shouldn’t still be there, it should have melted away to silence by now, but there it is. And therein is another component of Santana’s music, amply demonstrated on Moonflower -- the magic-realism of Latin folklore, the power of the supernatural in everything, and the tingling, electric sensation of listening to a really good Santana record.

To get the gist of what I’m saying, turn up the stereo good and loud. Do it in the car, in a parking lot, standing still. Don’t try to drive while appreciating guitar feedback to its fullest capacity for fulfillment. Do it in an armchair with a good pair of flat response cans, or, if no one’s home, open the fader and let the sound blast through your speakers. Moonflower offers high grade sonic transcendence on tap. For the experience of a live concert, listen to the careening beauty of “Black Magic Woman,” “Savor,” or “Soul Sacrifice” from the Abraxas era, complete with Carlos’ signature fuzz and effects, and the raucous, chaotic energy of Chepito Areas on percussion. Songs like “Europa” and “Transcendence” softly (but not quietly) offer the quintessential example of the Carlos Santana Sound in its starkly beautiful phrases and lengthy single-note passages of sustained sound. The latter features a masterpiece solo that you don't want to miss. With a snazzy snap and velvet touch, the subtle hooks of newcomers like “I’ll Be Waiting,” “Zulu,” and “Flor d’Luna” point to the coming years when Santana transitioned to pop and album oriented rock. If Caravanserai is the album that bridges the gap between Santana's acid rock genesis and their more advanced forays into further realms of jazz and progressive rock, then Moonflower is likewise the album that marks where Santana funnels all it learned from the second part of the journey, and strikes off in a new direction once again.

Friday, February 10, 2017

212. Weather Report / Legendary Live Tapes: 1978-1981 (2016)

On point! Four discs of hitherto unreleased live material from Weather Report's finest lineup. Pastorius recorded a healthy parade of studio LPs with the group and played dozens of gigs. His tenure is my touchstone for the Weather Report discography (I'm a native South Floridian, and admit heavy local partiality). I never saw them live, and I wore out the 8:30 album. That album's cushy overdubs and post-production soften the raw, affirmed talent in evidence on the live document. Given the Report's rep for slick and innovative studio work, I concur and take no issue there. But needless to say I am very happy that these tapes were assembled and released so we can hear them in the buff. Without hitting trading circles for soundboards and audience tapes, it's enough to pore over for a few years. Working through the first disc, my ears perk at Erskine's sparkling and aggressive work behind the drum kit, and his interactions with Jaco. Half the total sound is the rhythm section, hard to believe that only two people are carrying that. Nice notes are also included. While you wait for these to arrive in your mailbox, I heartily recommend the aptly titled Trio of Doom live disc with McLaughlin and Tony Williams.

Friday, January 27, 2017

211. Can / Tago Mago (1971)

Each of Can's albums is distinctly a product of the legendary ensemble, but each also presents its own direction and tone. Tago Mago is the first turning point. As the maiden voyage with Damo Suzuki, it opens the period of their most innovative work. "Paperhouse" displays the new chemistry: unintelligible motivic phrases are intoned, sometimes shouted by Suzuki. His strained voice is utilized for its value as a rhythm instrument, and also for texture. The caterwaul is entwined with Michael Karoli's grainy, insect-like guitar, while jitterbugging around Jaki Liebezeit's impeccable, discomfiting claptrap. Elsewhere, fragments of surreptitiously recorded rehearsals are draped over layers of arranged material in moody loops that crash together with the anxiety of cut-and-paste editing. "Mushroom" features a disorienting reversed vocal and further collisions of noise and melody. Moving into the dense heart of the album, "Halleluwah" is the archetype for Can's trailblazing approach to music. Suzuki mumbles and howls over noisy keyboards and chiming guitars, while Liebezeit parades in zombie fashion to the track's uncertain conclusion 18 minutes later. It's a 2-LP set, audacious and necessary. The music moves without being touched, as if by enchantment. If there exists a skeleton key to understanding Can and everything after, this is it.

Friday, January 20, 2017

Changes to this blog.

And management would like to announce.... a change in format! Henceforth, this blog will include my ramblings on all types of music, not just jazz. Don't worry, it's not a radical change in gears. I listen to all sorts of stuff, and while a lot of it could be classified as "jazz," much of it just isn't. Formerly I had several different blogs into which I would channel my thoughts, but I've decided to just combine them here because the world of 365 Dry Martinis seems to get the most attention. And my apologies for not updating my recent listening lists, or posting as often as I would like. But in the future, this should all improve. A health to you, dear readers, and thank you for dropping by. Feel free to say hello in the comments.

Saturday, September 17, 2016

210. Santana / Santana III (1971)

In the dictionary next to the word "essential," you'll find a picture of this album. Sandwiched between the seminal Abraxas and the revolutionary Caravanserai, Santana's third LP finds the band now very comfortable inside their invention, that unique fusion of Afro-Cuban rhythm with pan-Latin import and the ferocious, unrelenting pound of a psychedelic rock and roll band in full flight. If you liked Abraxas, don't forget to go the extra step and get this one, too. Because none were doing it in 1971, and none have done it better since. I think it's amazing how fresh and how mature the group sounds for just the third album, and yet, with all the swirling Hammond organ, raucous percussion and abrasive guitar, the thought of Caravanserai's chill embarkation for parts unknown almost brings a tear -- and by the way, I love Caravanserai. Compared to its immediate predecessor in the discography, III is rougher around the edges, a little more relentless in its pursuit of the groove, and maybe even a little less accessible. The music is fully cooked and raging. It sounds a lot like a live album, and the segues between tracks are so tight that they beg you to look for the seams. The audio quality on all available CD editions is stellar, and the "Legacy" edition contains a full live set from July 04, 1971 at the Fillmore West, plus extra studio sessions. Play it loud!

Saturday, January 2, 2016

209. Lionel Hampton & Stan Getz / Hamp & Getz (1955)

I suppose it's nice that by a happy accident of geography and scheduling, Hamp and Getz occupied the same place at the same time and afforded us a record. Hamp hits the sticks with a swinging ferocity that inspires Getz out of his cool cage in some unexpected chances. The pair battles through choruses and plods through a medley of ballads in a fair exposition of each's technique. It seems that Getz had to start running to keep up with the manic energy of the legendary vibraphonist. The two personalities make something of a strange cocktail, and I'd say the net result is more differentiated and less of a mutual product. The most exciting fireworks come during uptempo "Cherokee" and "Jumpin' at the Woodside." On the CD reissue, we have some extras, namely a mystery trombone player rumored to be Willie Ruff, but he doesn't really do much. The outtake of "Gladys" is a nice party favor, but, again, nothing special aside from where Hamp hits a clanger. I never like it when a reviewer describes something as "nonessential" but that's exactly what I've got here. The ingredients are enjoyable, but I'll continue taking my Hamp and Getz neat. The fine artwork on the cover is by the great David Stone Martin, reminding me that one of these days I'd like find a lithograph.

Labels:

1955,

bebop,

bop,

hamp and getz,

quartet,

quintet,

swing,

tenor,

tenor sax,

tenor saxophone,

verve,

vibes,

vibraphone

Saturday, December 12, 2015

208. Lionel Hampton / Hamp: The Legendary Decca Recordings (1996)

This two-disc set by Decca Jazz was produced by Orrin Keepnews and released in 1996. Its 36 tracks present two decades of music from a motley handful of bands, strong selections that amply demonstrate the bands' power and talent. Its main attraction for me is the inclusion of several scorching live cuts. But the track sequence isn't plagued by the problems inherent to retrospective collections like an excess of vocal numbers, songs in the same key, or long runs of tracks by the same group. The disc starts live in 1945 with a wild, careening orchestra whose high energy and charm inspires jealous visions of what a swing concert was like during the heyday. Throughout, the soloists are wide and varied (Jacquet, Gillespie, Shavers, Grey, et al) and, like many of the era's best known bands, Hamp's rosters are a veritable skeleton key to the door of jazz greatness. While Hamp is not an authoritative guide nor a complete collection by any means, it is an immensely enjoyable and astutely compiled survey of one of the 20th century's most influential bandleaders and his equally influential players. Recommended.

Wednesday, July 15, 2015

207. Stan Getz / Captain Marvel (1972)

Here, we find Getz in good form alongside the boys from Return to Forever. His own notes tell us it was Chick Corea who arranged the date, and most of the music is from his pen. But it is the tenor man from another era who craftily renders the smoothly stated leads that flavor the proceedings -- Stan Getz. He's a melodic monster, and a little like Zoot Sims, just can't seem to put a note wrong. At this point in his career, Getz's tone and the agility of his fingers were still intact, and his technique even thriving. So I hear the overlay of the players' contexts and their respective styles as the key to the session, with Getz relinquishing little of his modern cred, leaving the Corea contingent to provide the updated message. Remember, in 1972, Return to Forever was still newly formed. Miles Davis was active, the impact of fusion was unseen, and it was all still very fresh. Appreciate this disc for its personnel pairings as much as for its place in the later Getz canon. And it's got Tony Williams, reason enough for me to plop down for a listen.

Monday, June 22, 2015

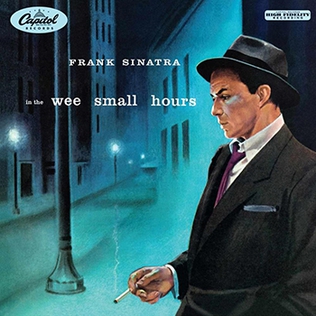

206. Frank Sinatra / In the Wee Small Hours (1955)

Though not as languished as 1959's No One Cares, this album of ballads sets the bar for melancholy, as well as being the first of the themed (and innovative) full-length LP's that Sinatra recorded for Capitol. Gordon Jenkins arranged and conducted on No One, but originally it was Nelson Riddle at the stand. The collaboration is magical. Riddle's restrained treatments underscore the mood of each lyric and magnify their impact. Sinatra expertly uses breath control and different vocal textures to interpret the material while Riddle's charts employ orchestral color at all the right incidental moments. Sinatra sings the passages carefully, sounding deeper and more mature than ever before. The frankness of songs like "Last Night When We Were Young," "I See Your Face Before Me," and "When Your Lover Has Gone" have secured In the Wee Small Hours a permanent place in the hearts of many fans. It remains one of his most satisfying and moving performances on wax. More than a routine set of ballads, it only takes a few notes to know that Sinatra is making these songs his own. At the same time, they're yours too.

Sunday, June 21, 2015

205. Coleman Hawkins with Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis / Night Hawk (1960)

.jpg) Enough has been said about Hawk's invention of the wheel when it comes to the tenor sax solo. His influence extends over both horizons and has touched untold numbers of musicians both directly and indirectly. But his work, especially that of the transitional 50's and early 60's, is also a lot of fun to listen to. Hawk's professionalism was so cool it was casual, his technique an enigmatic balance of technical innovation and instinct. Here, in a 1960 session for the Swingville imprint and recorded by Rudy Van Gelder, he is heard with fellow tenor Eddie Davis, Tommy Flanagan, Ron Carter, and Gus Johnson. The title track, 10 minutes of slow blues loosely organized around a theme, is a pickup number that demonstrates the players' knack for the above. The contrast between the tone and styles of Hawkins and Davis on tracks like "In a Mellow Tone" provides an added dimension. Flanagan is in top form playing tastefully between the leads, Carter and Johnson a sympathetic unit whose attention to the music goes beyond timekeeping. As with Duke Ellington Meets Coleman Hawkins recorded for Impulse two years later, a good result from such a meeting of the minds was not a foregone conclusion, but in both cases the outcome was memorable.

Enough has been said about Hawk's invention of the wheel when it comes to the tenor sax solo. His influence extends over both horizons and has touched untold numbers of musicians both directly and indirectly. But his work, especially that of the transitional 50's and early 60's, is also a lot of fun to listen to. Hawk's professionalism was so cool it was casual, his technique an enigmatic balance of technical innovation and instinct. Here, in a 1960 session for the Swingville imprint and recorded by Rudy Van Gelder, he is heard with fellow tenor Eddie Davis, Tommy Flanagan, Ron Carter, and Gus Johnson. The title track, 10 minutes of slow blues loosely organized around a theme, is a pickup number that demonstrates the players' knack for the above. The contrast between the tone and styles of Hawkins and Davis on tracks like "In a Mellow Tone" provides an added dimension. Flanagan is in top form playing tastefully between the leads, Carter and Johnson a sympathetic unit whose attention to the music goes beyond timekeeping. As with Duke Ellington Meets Coleman Hawkins recorded for Impulse two years later, a good result from such a meeting of the minds was not a foregone conclusion, but in both cases the outcome was memorable.Saturday, June 20, 2015

204. Don Cherry / Art Deco (1988)

Credited to Cherry, this session belongs to the same unit that worked together before Cherry, Haden, and Higgins historically joined ranks with Ornette Coleman. It's a beautiful straight set, comprised of cooly executed standards, originals, and several Coleman covers. The quartet is familiar and tight. I haven't listened to much of James Clay's past work, but now I wish I had more of it on hand to explore. His deep, supple lines in "Body and Soul" put a fresh coat on the old song, mixing wry bop phrasing with bursts of unexpected tonal color and bluesy swagger. Cherry takes a rest while Higgins and Haden nimbly sidestep one another before Haden builds a short solo. The ensemble picks up again behind Clay's last chorus and the plaintively emotive outro for solo tenor. Monk's "Bemsha Swing" comes next, where Cherry and Clay get most of the spots, but leave room for Higgins. Higgins, Cherry, and Haden each get time alone on "Passing," "Maffy," and "Folk Medley," quiet, introspective spaces that give listeners a chance to appreciate their individualism. Eight-bars-and-blow gets old, I agree, but these renderings sagely belie that trope with wit, spirit, and a genuine enjoyment for the music Do you love great jazz? Find it, buy it.

Sunday, June 14, 2015

203. The Jeff Lorber Fusion / Wizard Island (1980)

If you don't listen to jazz, you've probably heard Lorber's music on the Weather Channel while checking your local forecast! The back catalog is a bit more interesting, but not by much. This record was a #1 seller for Arista, and it sounds every bit the part. Cast in the same mold as the heavy hitters like Hancock, Corea, Clarke, et al, it lacks the trailblazing and depth found in those acts (Corea guests on "Rooftops"). Selections are heavy on the funk and Arista Records' special sauce, a superb studio product. It's got a lot of production on it and in spite of the funky corners, some of the songs do take on a two-dimensional pop simplicity. But if you're a fan of good bass playing or vintage synths like Minimoog and the Sequential Circuits Prophet 5, Lorber's album might interest you. I'm not a big fan of soft jazz or heavily produced wallpaper, but I do spin it sometimes. Dennis Bradford and Danny Wilson get high marks for drums and bass, respectively. Bland as this example may be, funky fusion grooves were an entry point for countless musicians of the 70's and early 80's, and Wizard Island does well to show you the ropes.

Labels:

1980,

arista,

chick corea,

danny wilson,

dennis bradford,

funk,

fusion,

jay koder,

jeff lorber,

jeff lorber fusion,

kenny gorelick,

minimoog,

paulinho da costa,

synthesizer,

wizard island

Sunday, May 31, 2015

202. Flying Island / Flying Island (1975)

The self-titled debut from the fruitful but short lived Connecticut group Flying Island has excellent music to offer and deserves wider recognition. Things begin with a sharply executed "Funky Duck," but the material takes interesting turns into weirder territory and more aggressive textures like on "Flying Island" and "I Love to Dance." The music proceeds across shifting time signatures in tradeoffs between Fred Fraioli's electric violin and keyboards by Jeff Bova. Fraioli speaks in squalling, anthemic strokes, sometimes smooth, sometimes menacing, bookended by his fiery runs and escalated, wailing solos. Also present are guitarist Ray Smith, bassist Thom Preli, and drummer Bill Bacon. Smith and Bacon emerge as superb players that make the album much heavier than your typical mid-70s fusion outing. After the violin-keyboard pyrotechnics are over, their work is often the force that distinguishes the band from dozens of similar acts. Flying Island and the follow-up Another Kind of Space should interest fans of higher profile names in '70s fusion like Jean-luc Ponty, Weather Report, or Mahavishnu Orchestra. The musicians are competent and talented, and the total package is professional and well rehearsed. Yet it is not without the spark needed to bring a studio take home for the listener. Highly recommended!

Labels:

1975,

bill bacon,

clavinet,

debut,

electric guitar,

electric piano,

flying island,

fred fraioli,

fusion,

jazz rock fusion,

jeff bova,

organ,

quintet,

ray smith,

review,

sextet,

thom preli,

vanguard,

violin

Monday, May 25, 2015

200. Giger Lenz Marron / Where the Hammer Hangs (1976) & 201. Giger Lenz Marron / Beyond (1977)

Peter Giger's career is full of wild one-way streets. It's like he can do it all, equally at home playing it straight, or rattling through an assortment of percussion instruments in jams of thorny, implacable experimentalism. Where the Hammer Hangs and its sister slab Beyond are just a short stop in his considerable career. Both albums are presently out of print, and are obscure considering his other accomplishments in major jazz circles. If you're familiar with Giger's work in more mainstream engagements, it's probably best to come at these from the Dzyan angle (which was actually my introduction to Giger some time back). Hammer and Beyond were released on his own Någarå label, and stylistically speaking, pick up right where the Dzyan vehicle left off. There are differences. Just like Dzyan, you will hear searching group improvisations, hints of Eastern rhythm and instrumentation, druggy, reverb-laden guitar forays, and plenty of crossover from the above. But Giger Lenz Marron has fewer pedestrian handholds, less that is familiar, and seemingly no rules except for limitations imposed by the instruments themselves. It's like the ingredients of a Dzyan album, but set in a different project removed from whatever restriction was imposed by the group moniker. Although not a major pit stop on the timeline of such prolific musicians as these, the GLM trio interests me for its freedom of form as well as its connections to several trends that first emerged ten years prior. It proves that jazz is a many faceted thing that will continue to be wrought anew by the creative hands and minds that shape it.

Peter Giger's career is full of wild one-way streets. It's like he can do it all, equally at home playing it straight, or rattling through an assortment of percussion instruments in jams of thorny, implacable experimentalism. Where the Hammer Hangs and its sister slab Beyond are just a short stop in his considerable career. Both albums are presently out of print, and are obscure considering his other accomplishments in major jazz circles. If you're familiar with Giger's work in more mainstream engagements, it's probably best to come at these from the Dzyan angle (which was actually my introduction to Giger some time back). Hammer and Beyond were released on his own Någarå label, and stylistically speaking, pick up right where the Dzyan vehicle left off. There are differences. Just like Dzyan, you will hear searching group improvisations, hints of Eastern rhythm and instrumentation, druggy, reverb-laden guitar forays, and plenty of crossover from the above. But Giger Lenz Marron has fewer pedestrian handholds, less that is familiar, and seemingly no rules except for limitations imposed by the instruments themselves. It's like the ingredients of a Dzyan album, but set in a different project removed from whatever restriction was imposed by the group moniker. Although not a major pit stop on the timeline of such prolific musicians as these, the GLM trio interests me for its freedom of form as well as its connections to several trends that first emerged ten years prior. It proves that jazz is a many faceted thing that will continue to be wrought anew by the creative hands and minds that shape it.

Saturday, May 9, 2015

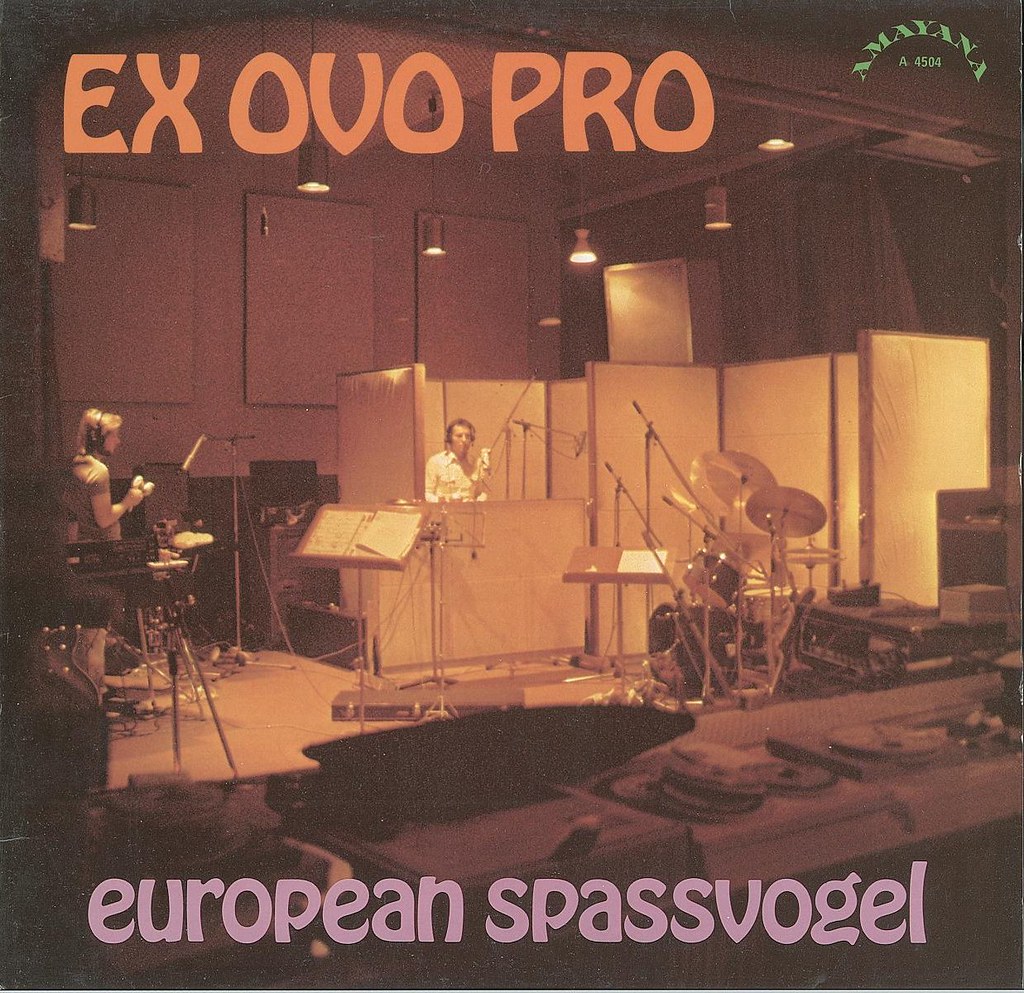

199. Ex Ovo Pro / European Spassvogel (1976)

I don't hear enough of the European jazz scene, past and present, simply because of the music's more limited availability where I live. Thankfully, the web makes the world a little smaller and I was able to locate and hear this out-of-print gem from the Amayana label. European Spassvogel ties a lot of pieces together and after listening to many American groups from the same era, it's refreshing, I really like it. The music is exploratory with anchors in moody vamps and dark melodies. Thankfully, funk is only an ingredient, and the band doesn't dwell on it indefinitely, frequently moving away from it. Wild extemporizations of Mandi Riedelbauch ("In a Locrian Mood") are free and noisy, but the band is really tight. Harald Pompl pounds his traps all around the beat, stuffing the cracks with a unique assortment of percussion and technique. Max Kohler's growly electric bass pours the foundation, and while Pompl does his thing, Kohler keeps time. Hans Kraus-Hubner proviides electric piano, often leading, sometimes coaxing the soloists. It's just a good, chill listen. The songs are concise, and the sides wrap before you can get distracted. If you're like me and get burned out on purely funk-based fusion, this could be what you were looking for.

Labels:

1976,

amayana,

electric guitar,

electric piano,

european spassvogel,

ex ovo pro,

fusion,

germany,

hans kraus hubner,

harald pompl,

jazz,

jazz rock fusion,

mandi riedelbauch,

max kohler,

review,

roland bankel

Saturday, March 28, 2015

New content coming soon

This last year was tumultuous as I moved my family moved across the country, twice. We're mostly settled now, and I should find some more time to update 365 Dry Martinis with my thoughts (if you're interested in what I am listening to each day, without reviews, you can still find the material added daily in a list by following the link at the top of the page). Yes, this space has been quieter than usual, but my daily life has been far more chaotic than usual! I'm excited, though. I've got a lot of interesting things to discuss.

Look out for upcoming reviews of LPs by Giger Lenz Marron, BBL, Carla Bley, Kandahar, Nu Creative Methods, and more. Hard bop and classic jazz are still my bread and butter but I'm going to stretch the horizons of this blog and see where it goes. I love that stuff, too. Hang in there.

Look out for upcoming reviews of LPs by Giger Lenz Marron, BBL, Carla Bley, Kandahar, Nu Creative Methods, and more. Hard bop and classic jazz are still my bread and butter but I'm going to stretch the horizons of this blog and see where it goes. I love that stuff, too. Hang in there.

Saturday, March 21, 2015

Saturday, December 27, 2014

198. Frank Wess / Opus in Swing (1956)

This pianoless quintet led by the flute of Frank Wess also lacks his other instrument, the alto sax. Accordingly, he's in top form whether it's pounding high notes in the blue gloom of "Southern Exposure" or adding harmonic color to the serpentine leads of "Somewhere Over the Rainbow." Also moonlighting from the Basie Band are Eddie Jones and Freddie Green who keep time with Kenny Clarke so tight it's telepathic. The quintet excels in the same music that Basie's bands made famous. Like Basie's, their combo has an undeniable group dynamic, but every man is heard as his own solo artist. Together, they drive the music with one mind, then shine forth as individuals during the moments when one man stands alone. It's impossible to appreciate one quality without noticing the other. Kenny Burrell is notable. Listen to "East Wind." Green trades chording for a more pianolike approach that walks, while Klook keeps time with the cymbals and Wess sketches the heavy mood with dense vibrato. When he lays out, Burrell bursts the seams with bluesy runs and relevant single note phrases that underscore the character of the melody and polish the rhythm. It's choice stuff, a potent brew of Kansas City swing that has been seasoned with the developments of postwar New York.

Friday, November 7, 2014

197. Steely Dan / Gaucho (1980)

Gaucho is the last album before the Dan's 12 year hiatus. It's the capstone of the original run, a grooving foil to Aja's majestic sophistication, and the proverbial semibreve rest in the ongoing saga of the Becker/Fagen partnership. Instead of trying to reinvent the wheel, Gaucho swaps Aja's complexity for simple charts and chill vibrations that recall classic rock, rhythm, and soul. Here, the down tempo is on tap and the beats play straight ahead. Hear "Babylon Sisters" shimmer with rich sonority, lush background vocals and immaculately layered overdubs, and you get the picture. Gaucho is also notable for the drum machine (engineer Roger Nichols' "Wendel") lending additional consistency to the already smooth track sequence. If you like Steely Dan, then chances are you won't be disappointed by the fare on Gaucho. But at the same time, while these are unmistakably "Steely" tunes, I think it is also the most stylistically distinct album in the catalog. As always, make of that what you will.

Sunday, August 17, 2014

196. Buddy Collette / Live from the Nation's Capital (2000)

Buddy Collette was an originator on the West Coast jazz scene. He cofounded the Chico Hamilton Quintet and devoted his time to education, as well as composing and performing. This live disc from 2000 captures a Collette program for the ages, and its disparate contents cover the arc of his career. Performance and audio production are slick, typical of groups billed on the national stage. There is a lot to enjoy. Professionalism aptly describes the soloists, who play snappy, expressive lines that don't disrupt the cascading harmonies. Arrangements are by several including Collette. No matter the arranger, though, the playlist is unified by breaking the group into combos, building tension, and using the whole ensemble for bursts of energized dramatics. Nothing new under sun as far as big band goes (Gerald Wilson or Sam Rivers orchs are more my style) but the infectious bounce on tracks like "Mr. and Mrs. Goodbye" hold a warm sentimentality for a bygone era while others, like the Afro-Cuban rhythm of "Andre" or improvs on "Blues #4" keep the pace and make good use of variety. Live from the Nation's Capital isn't the most essential big band record in my collection, but it offers a lot of good stuff and demonstrates (in a very straight way) the wide array of styles that Collette worked in throughout his career.

Monday, June 23, 2014

Too hot.

I always feel irritated when a blogger I like apologizes for being too busy to post. It's completely unnecessary to tell me that! So I'd like to give you, faithful readers, the same opportunity to roll your eyes. I've been working a chaotic new schedule while listening mostly to Miles Davis, bluegrass, and reggae. I have no time to review records but I'll try to add some updates here in the coming days.

In the meantime, hang out with the Specials.

In the meantime, hang out with the Specials.

Wednesday, May 7, 2014

195. Jazz Anecdotes by Bill Crow (1991)

This music we have come to call jazz is long and storied, its course determined by thousands of musicians, singers, bandleaders, producers, patrons, and hangers on. Music is more than harmonically related pitches that sound off in regularly timed intervals. It's a living and growing mode of expression, a self-description of our culture. a sentimental record of our times. Bill Crow's Jazz Anecdotes is exactly what the title implies. Drawn from many sources, readers are treated to a rich assortment of personal recollections, rumors, legends, inside jokes, and more than a few stories with very long legs. In his introduction, Crow shares a fundamental truth about storytelling: every good tale has a life of its own, eclipsing even the storyteller. In this way, real or imagined, the contents of Crow's compendium leap right off the pages, straight into the annals of popular culture. I'll equate jazz with my favorite sport, baseball. A listener can enjoy a song without knowing the musicians much like how a spectator can enjoy a ballgame without knowing too much about the players. But understanding the personal dimension of their collective small-game and their colorful arc of backstory enriches the experience tenfold. If you stay interested for your entire life, it's more than 18 guys on a diamond. The sport actually fulfills the obligation of a cultural phenomenon in which the spectator is a willing participant in the creation of its legend.

But back to jazz... Through Crow's work, which is subdivided into manageable sections covering certain musicians or styles, or certain aspects of being a musician, you get all the behind-the-scenes gossip, juicy tidbits, and wild memories of the women and men who made the music happen. In other words, the material is so vivid, it's as if the subjects are right there in the room, talking to you. In his acknowledgements, Crow thanks Nat Hentoff, whose book Hear Me Talkin' to Ya is a similar work that bears mention here. Likewise, and with a stronger recommendation for its beautiful prose and sense of relational self identity, please see Living with Music: Ralph Ellison's Jazz Writings. I'll close by saying this: When I put the book in the nightdrop and left it there to resume a lonely life on the shelf for two or three more years, whenever the next patron should come along, I actually said goodbye. Startlingly, as I drove off in my car, I felt like someone heard me.

But back to jazz... Through Crow's work, which is subdivided into manageable sections covering certain musicians or styles, or certain aspects of being a musician, you get all the behind-the-scenes gossip, juicy tidbits, and wild memories of the women and men who made the music happen. In other words, the material is so vivid, it's as if the subjects are right there in the room, talking to you. In his acknowledgements, Crow thanks Nat Hentoff, whose book Hear Me Talkin' to Ya is a similar work that bears mention here. Likewise, and with a stronger recommendation for its beautiful prose and sense of relational self identity, please see Living with Music: Ralph Ellison's Jazz Writings. I'll close by saying this: When I put the book in the nightdrop and left it there to resume a lonely life on the shelf for two or three more years, whenever the next patron should come along, I actually said goodbye. Startlingly, as I drove off in my car, I felt like someone heard me.

Tuesday, May 6, 2014

194. Louis Jordan & His Tympany Five / Choo Choo Ch'Boogie (1999)

Choo Choo Ch'Boogie is another terrific compilation of golden era R&B from the ASV/Living Era imprint. Jordan was a versatile vocalist whose act ran the gamut from vaudeville to jump to gut-busting blues. His smooth delivery and expertise with turning a phrase took dancers from cutting figures on the floor to falling down laughing. He was also an altoist with a nimble technique whose reserve of power drew comparisons to Earl Bostic. The set is a good representation of his repertoire from 1940-1947. In crisp audio, it includes famous numbers like his own "Caldonia," "Five Guys Named Moe," or "Let The Good Times Roll." But the playlist also has novelties like the hilarious calypso with Ella Fitzgerald (both ex-Chick Webb), "Stone Cold in de Market" or "What's the Use of Getting Sober (When You're Gonna Get Drunk Again)?" No stranger to the drink whose wife Fleecie twice tried to kill him by stabbing, Jordan sings these with confidence! His blues are followed by his alto, with nary a breath between verse and chorus. "Ration Blues," "Somebody Done Changed The Lock on My Door" and "Ain't that Just Like a Woman," show Jordan working his charm with sly double meaning and steamy intent. Fans of early rock and roll or Chicago blues will appreciate Jordan's work, and this is a fine place to start. Babs Gonzales, Slim Gaillard, King Pleasure, all similar.

Thursday, April 24, 2014

193. Mads Vinding Trio / Daddio Don (1998)

A while back, I recommended an album with Mads Vinding to a friend who loves the upright bass. It's his favorite instrument. We chatted about the Danish bassist and both agreed he's a hard one to not like. A few weeks later he gave me some CDs that, for whatever reason, didn't pan out for him the way he expected. It happens. But I was thrilled because among them was Daddio Don. I listened to it for the rest of the afternoon before promoting it to a coveted spot in the rotation of my daily commute. Vinding is impossible to keep up with, the tireless recording and performing artist for whom the word "prolific" seems inadequate. He's all over the map, discographically speaking, but always right where you need him with the soulful interplay, keen rhythmical knack, and melodic inventions that surpass keeping time for the time's sake. He has a sixth sense for interplay, or a humble ear for the group dynamic, always listening to what the other musicians are doing. I appreciate his earnest touch with the blues and immediate facility for navigating uptempo and bebop that remind me of Ray Brown (another favorite musician). His choruses are not boring, they're more like short songs. To paraphrase C. Michael Bailey's piece for AllAboutJazz.com, Vinding is like the Nordic George Mraz, expressing himself with a confident stride and robust tone that tricks the ear into hearing a full rhythm section where none is present. The trio is comprised of Vinding, drummer Alex Riel, and pianist Roger Kellaway. Kellaway has a sensitive understanding of the piano's dynamics, and moves with irresistible swing.

More importantly, Kellaway has a penchant for odd time signatures (the album is titled for Don Ellis), and all three musicians are comfortable breezing through meters like Kellaway's "Seven," or Thad Jones' "A Child is Born" in 11/8. Riel's timekeeping is sumptuously alert. His dreamy brush work is punctuated by pertinent, percussive accents and taut interjections on the snare that make the emotive and pensive, often introspective set as lush and flush as a well arranged quintet. "How Deep is the Ocean" is intriguing, demonstrating the shared chemistry of the trio. It's a touch faster than is typical, and the order of its open sections are negotiated as you hear them. It typifies the musical cooperation which is the album's hallmark. If you're the type of listener that enjoys quiet spaces with tricky corners, a shared creation of three musicians that reveals the sheer clumsiness of language when describing a mere "piano" trio, then Daddio Don needs to be on your list. And if you try it but you don't enjoy it, perhaps you can pass it on to a friend.

| Image courtesy of soundcloud |

Saturday, April 19, 2014

192. John Scofield - A Moment's Peace (2011)

Like any other artist, John Scofield is no stranger to the ballad, which is amply represented in his back catalog and live repertoire. But A Moment's Peace is the guitarists first album consisting entirely of ballads (Scofield's albums are big on themes, anyway). It's a really enjoyable set of standards with Brian Blade, Larry Goldings, and Scott Colley on hand to help out. They deserve congratulations because while anybody will recognize these tunes, when the band locks in with Sco in the lead for emotive rushes like "I Want to Talk About You," or the slippery bends and bluesy explorations of "Gee Baby Ain't I Good to You," it's still pure magic, despite the age of the music. Scofield's guitar is heard in a judiciously reverberant, tone saturated signal that is occasionally augmented by simple effects like tremolo, or Scofield rolling the volume knob for shading and dynamics. I love that technique, especially when Blade is playing sympathetically, and Goldings starts to use the draw bars in the same track... the cumulative effect of both instruments pulsing together creates a blissfully disorienting sonic texture that shimmers like light reflecting on a water surface. A Moment's Peace was good when I heard it three years ago, and it is getting better. Highly recommended.

Friday, April 11, 2014

191. Fred Hersch - Alone at the Vanguard (2011)

Hersch plays in his characteristically slick and lyrical style in this collection of live, solo recordings. The gently meandering set is just over an hour long but

was culled from an entire week of performances at the Vanguard in 2010. Hersch's back catalog of superb trio records has given him all the leeway that could be expected from the trio format, but alone, he is free to wander a little farther from the yard, in both time and route, as with Sonny Rollins' "Doxy," or the elegant salute to Thelonious Monk's "Work." In the absence of the drums and bass, he develops sweeping melodic arcs in each piece, and displays refined senses of harmony and dynamics. With several numbers he tips his hat to inspiration from friends and figures like Robert Schumann, Bill Frisell, and Lee Konitz. My favorite piece is the disc's opener that I know as a favorite Frank Sinatra song (although it has been covered countless times since). "In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning" is rendered so poignantly as to touch the emotional depth achieved by Sinatra on the 1955 album.

Labels:

2010,

2011,

alone at the vanguard,

fred hersch,

jazz,

live,

palmetto,

piano,

review,

solo,

tribute

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)