Recent listening, current

Archived listening, 2013-2016

Saturday, September 21, 2013

141. Monty Alexander, Ray Brown, Herb Ellis / Triple Treat (1982)

For various reasons, the cover of this recording seems oddly appropriate. A photograph of a three-scoop ice cream sundae makes a cheeky pun for the piano trio's sweet and sometimes quirky set of tunes like Blue Mitchell's "Fungi Mama" (with fun quotes by Ellis, and some jangly syncopation by Alexander) or the hot side-opening "(Meet The) Flintstones." Monty Alexander fills the piano chair and I don't think he sounds one bit like Oscar Peterson, in spite of Brown and Ellis being longtime members of that musician's group. The other music on the album is equally sweet and creamy, as with the sumptuous "Body and Soul" and "Sweet Lady," or swinging "When Lights are Low." Also notable is the title track, the "Triple Treat Blues." Chemistry, relaxed atmosphere and slick, baton passing choruses of these three musicians make a buoyant and memorable session that is out of print but worth seeking out. If you enjoy this lineup, be sure to check out their other albums, as well.

Thursday, September 19, 2013

140. Tal Farlow / The Swinging Guitar of Tal Farlow (1956)

This blues and bop trio date with Farlow, Eddie Costa and Vinnie Burke is easy to listen to, and closer listening reveals a lot going on. The styles of Costa on piano and Farlow's guitar dovetail nicely. Farlow's eloquently phrased and heavy swinging choruses are followed by those of Costa, who plays in a hard-hitting, single-note style and is very rhythmic. Farlow uses the occasional slide, as in "Yardbird Suite," but instead of relying on an arsenal of tricks and stock licks, he is adept in inventing on the fly. The improvisations literally flow from the speakers like they're on tap. With so many ideas being tossed around, there's a lot of interplay between the piano and guitar. Burke plays the bass more or less steadily throughout, occasionally getting a chorus his own. The outtakes of "Taking a Chance on Love," Yardbird," and two (!) extra takes of "Gone with the Wind" are all so good that it's difficult to say how they determined a master. At any rate, the bonuses are much appreciated by this listener! Admirers of Ahmad Jamal's drumless trio with Ray Crawford, the Aladdin dates of Art Pepper, or the Modern Jazz Quartet should take immediately to the music herein.

Monday, September 16, 2013

139. Jimmie Lunceford / Strictly Lunceford (2007)

Today, Lunceford is lesser known than his peers. This four-disc set from Proper provides a good introduction to Lunceford's work across numerous record labels. Audio and notes in the accompanying 28-page booklet are commendable. Considering how good this band was, any neglect by record companies or listeners seems a real shame: Lunceford's band replaced Cab's at the Cotton Club, an appointment that was no mean feat. Then and now, they have a lot to offer. The famously diverse repertoire uses vocals, novelty songs, and barn burning dance music on par with other great orchestras. Lunceford's driving two-beat pulse appears in tracks like "Lunceford Special." I find it instructive to compare arrangements by Sy Oliver to those done by his successor, Billy Moore, as well as the other arrangers in the group. All crackle with originality. I love Oliver's muted brass ensemble in "Chillun, Get Up!" but Wille Smith's radical take on "Mood Indigo," replete with staccato phrases and soaring three-octave accompaniment on reeds and brass, isn't to be tangled with, either. On every track, the soloists are poignantly melodic and very sweet, like Eddie Tompkins on trumpet or the aforementioned Willie Smith on alto. The eagle-eyed (or eared?) listener will also spot the likes of Snooky Young and Gerald Wilson. Don't overlook this set!

Labels:

2007,

big band,

billy moore,

columbia,

decca,

eddie tompkins,

gerald wilson,

jimmie lunceford,

proper,

snooky young,

strictly lunceford,

swing,

sy oliver,

victor,

willie smith

Friday, September 13, 2013

138. Roy Eldridge / The Nifty Cat (1970)

Roy Eldridge as leader? Has the moon come down? He didn't lead much, didn't even record much after 1960, and I wasn't aware of this disc until spotting it at my library. The personnel is interesting. There's Budd Johnson whose skills in arranging, tenor and soprano sax are the perfect fit for Eldridge's brand of jump and small group swing. The bass is by Tommy Bryant, a musician of great skill and style, and one who seems underappreciated today. On drums is perennial session man Oliver Jackson, piano is 'Countalike' Nat Pierce, and perhaps my favorite man on the album is Benny Morton on trombone. His inventory of different sounds and licks is inexhaustible and the 'bone brings a touch of old school class to the proceedings (check him out on the lazy "Jolly Hollis," or "Ball of Fire"). "Cotton" is a deep and stormy blues carried by an appealingly mysterious piano and bass figure. Eldridge sings the humorous blues "Wineola," also getting a nice solo in the tune, and things really cook with Eldridge's "Ball of Fire," filled by a lot of riffing and Eldridge showing off his famous range. The closer is the title track with solid work from everyone. I especially enjoy Eldridge's first solo. There's a good mood throughout the set, and I'm thankful for this disc given how much the trumpeter worked but did not record. It's definitely worth finding.

Thursday, September 12, 2013

137. Arnett Cobb and Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis / Blow, Arnett, Blow! (1959)

This Prestige date was something of a 'return' for Cobb, who had been recently injured and was retired during recovery. Fans of Mr. Davis should enjoy the album thoroughly because it's exactly the same band as the Cookbook sessions, plus Cobb. Every cut is a wild give and take between Cobb and Davis, a battle for sure. Shirley Scott, making heavy use of the drawbars and tremolo, throws gasoline on the fire more than once. The choice of an organist over a pianist makes a big difference in the total sound and Scott definitely has some good licks. The quintet setting is almost too small to contain the horns, and it does get noisy, but the arrangements are tight. It's well worth seeking out for fans of early soul jazz, or Texas tenor, or anyone studying the small group work of Cobb or Davis who were also well known as big band soloists. The opening chestnut "When I Grow Too Old to Dream" is very nice, also take a look at "Dutch Kitchen Bounce" and "The Eely One." I wonder, is that title a reference to Bud Freeman? Maybe someone in the blogosphere can tell me. One word for this album? Hot!

Labels:

1959,

arnett cobb,

arthur edgehill,

eddia lockjaw davis,

george duvivier,

jazz,

organ,

prestige,

quintet,

review,

rhythm and blues,

shirley scott,

soul jazz,

tenor sax,

tenor saxophone,

texas

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

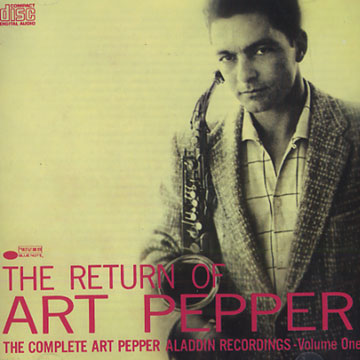

136: Art Pepper / The Return of Art Pepper: The Complete Aladdin Recordings, Vol. 1 (1988)

There are two groups here, recorded 1956 and 1957. The first group features Pepper straight out of prison and recording again. It's a somewhat unbalanced group and Pepper's style is intact but languishing. This makes instructive listening, considering how hot he could be on a good recording, I find it fascinating to see between the lines for a few moments while his fingering isn't as nimble and the ideas are developing more slowly. There's some good balladry ("You Go to My Head") and some flashy piano and trumpet from left coasters Russ Freeman and Jack Sheldon. The gems, for me, come in the pickup band on tracks 11-15 with Joe Morello and Red Norvo. This group was put together on the fly, presumably with little or no rehearsal, and the miracle is that it's a really tight date with a really positive chemistry. Morello was leader. "Tenor Blooz," "Yardbird Suite" and "You're Driving Me Crazy" show Pepper's style in full flight. Also, Norvo and Carl Perkins, and Pepper's interplay with Perkins, are not to be missed. If I had the choice to keep one disc out of this Aladdin set, The Return of Art Pepper might not be my first choice, but the Morello/Norvo recordings redeem it.

Labels:

1956,

1957,

1988,

aladdin,

alto,

alto saxophone,

art pepper,

bebop,

blue note,

bop,

cool,

joe morello,

quintet,

red norvo,

sheldon,

the complete aladdin recordings volume 1,

the return of art pepper,

west coast

Sunday, September 8, 2013

135. Ryan Kisor / Minor Mutiny (1992)

The cover, which apes Chet Baker, first grabbed me. I saw a young guy, similar features, sport coat, trumpet, and dramatic lighting. I thought, okay, let's try this out. The second thing, first hearing then reading, was the personnel including Ravi Coltrane, Lonnie Plaxico, Michael Cain, and either Jeff Siegel or producer Jack DeJohnette on drums. It's a sweet debut, a sort of double debut if you count Siegel. I was immediately swept up by the beautifully lonesome "One For Miles," which evokes Davis' "Basin Street Blues" from Seven Steps to Heaven. Kisor pays through the mute and it's a spot on, glowing tribute. My reaction was, "If this guy doesn't sound like Miles!" Yet in spite of Kisor's obvious reverence for the master, the performance isn't cliche and the style is all his own. Then there's the work by Ravi Coltrane on tenor and soprano. His tone and intonation on soprano are exemplary and the choruses take possibly the most unique voice in the group. Juxtaposition of drummers Siegel and DeJohnette do not ruin the continuity. Siegel is fantastic, playing responsively in intricate patterns all around the beat, and doesn't suffer for following an experienced musician like DeJohnette. You'll find that Siegel's playing even starts the melancholy album (there is some great mood on this disc), and he is only supplanted by DeJohnette on two tracks.

Labels:

1992,

columbia,

debut,

jack dejohnette,

jeff siegel,

lonnie plaxico,

michael cain,

minor mutiny,

quintet,

ravi coltrane,

ryan kisor,

soprano sax,

tenor sax,

tenor saxophone,

tribute,

trumpet

Saturday, September 7, 2013

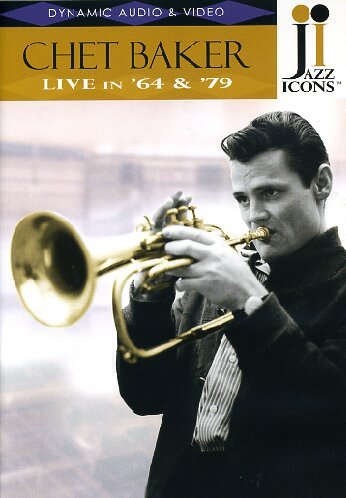

134. Chet Baker / Live in '64 and '79 (2006)

Baker's music definitely matured, although his development is sometimes difficult to appreciate given how his drug habit impacted his life and performances. This DVD from Jazz Icons shows him playing with two European groups, 15 years apart. In the '64 quintet I sense tension between the underplayed Baker and overactive pianist Rene Utreger, who is constantly throwing heavy handed chords at the end of Chet's phrases, sometimes before they appear to be completed. It's like a leadership dispute, and the band or producers clearly have their own ideas about who falls where. In spite, Baker manages a lovely "Time After Time," though the quintet's take on "So What" seems like a missed opportunity. Baker has trouble finding space to express himself and fights with the group, and also has difficulty with the intonation. The second performance is from '79 and begins with an interview that segues into "Blue Train," in progress. Baker says his lyrical approach to improvising has become more subtle with experience and the performance reflects this. The drummerless quartet is much more together than the '64 group, thankfully, and Baker's rich sumptuous tone pervades the set. Although "Blue Train" is truncated (which stinks, because what we do hear is beautiful), we get a heavy swinging and creative take on "Softly As In a Morning Sunrise" with Baker's smoothly flowing melodic improvisation, the occasionally interesting turn of a chord, and overriding melancholic appeal. Also notable are pianist and vibraphonist Michele Graillie and Wolfgang Lackerschmid. I like this installment of Jazz Icons for the contrast it provides between a younger Baker and an older, perhaps wiser player with a more respectful band.

Labels:

1964,

1979,

2006,

chet baker,

cool,

film,

jazz icons,

live in 64 and 79,

michel graillie,

quartet,

quintet,

rene utreger,

review,

trumpet,

vocal,

vocalist,

wolfgang lackerschmid

Friday, September 6, 2013

133. Roland Kirk / We Free Kings (1961)

This early album by Roland Kirk demonstrates some of the things he became known for a bit later on. It's a polished, enjoyable, and provocative album. Most notably, throughout the blues and soul inflected set, he plays two or sometimes three instruments at once and switches between them at lightning speed. While blowing the blues on the flute, he likes to screech, howl, and sing along. There aren't any drop-ins from the board, no spliced takes. Obviously with one man filling four chairs, the arrangements revolve around him. As a testament to his talent, it works seamlessly. Kirk has an inspiring technique and sweet tone on all instruments. His style of improvising, I think, clearly departs from the Coltrane bag he was once lumped into. The band is Hank Jones or Richard Wyands, drums is Charlie Persip (great choice), and bass is Art Davis or Wendell Marshall. Through his technique and instrumentation, Kirk puts a unique spin on old tunes, and kicks out his own compositions, as well. After this album, Kirk's journey continued to seek new directions, ever expanding, ever exploring. We Free Kings isn't just nice for listening, it's also nice for perspective. It shows his music is steeped deeply in blues and bop, but the trajectory for future dates would always be farther out than before.

Labels:

1961,

art davis,

charlie persip,

flute,

hank jones,

hard bop,

manzello,

mercury,

quartet,

review,

richard wyands,

roland kirk,

stritch,

tenor sax,

tenor saxophone,

verve,

we free kings,

wendell marshall

Thursday, September 5, 2013

132. John Coltrane / Fearless Leader (2006)

Coltrane's Prestige albums have been available in various formats since the 1950s. Another chapter in the flood of repackaged Coltrane on CD, Fearless Leader places his earliest recordings as leader in chronological order. This allows serious listeners to study his development as composer, arranger, and stylist without having to track down the individual records. Moreover, by removing these recordings from their in-album sequences, they exist in a proper or at least more authentic musical context. They transcend the supposition that is imposed by arbitrary sequencing and stand their ground against one another, in the order they were created. Listening to the whole box, or at least a good chunk of it in one sitting, is a rewarding experience. From the outset, Coltrane's groups are well rehearsed and the arrangements are tight. Throughout the progression, it's exciting to hear Coltrane's tone become more sonorous, his technique sharper, more assured. In addition to the leader, there's Paul Chambers, Art Taylor, Red Garland, Mal Waldron, Freddie Hubbard, and others. We hear them take some excellent shots at the blues, as well as Coltrane's peerless balladry in classic chestnuts like "Lush Life" (Donald Byrd around the 9-minute mark, wow), and some early sheets of sound ("Black Pearls," "Russian Lullaby"). Across six discs, there's too much to discuss here. Somebody could, and several people have, written books on this music. The concept of the six-disc set, plus accompanying booklet with copious photos and notes, make it a really attractive package. Unless you want the individual albums, I'd say this is a core collection item.

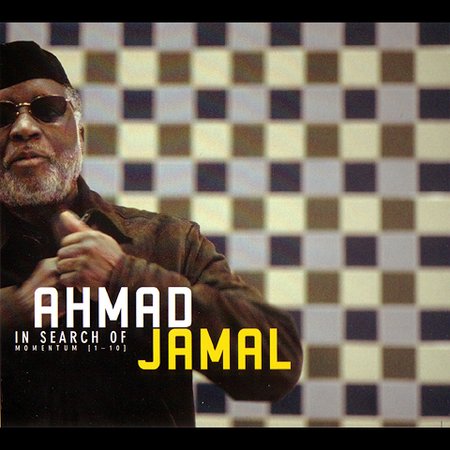

131. Ahmad Jamal / In Search of Momentum (2003)

Jamal is an excellent player, strong as ever and still developing past age 70. In Search of Momentum is a prime example, the kind of record that makes other new things feel stale (here "new" is 2003). His enthusiasm for contrasting percussive block chords with what I like to call 'negative space' on the piano is matchless. His style is ever more rhythm driven, and it's full of energy for standards like "Where Are You." In the opening "In Search Of" he plays with some sly quotes that bring a grin. In "Should I?" he characteristically mixes a heavy left hand with intermittent flourishes of the right, building to thundering crescendos a la Erroll Garner, then reclining in moments of delicate quietude. He works closely with his excellent trio, who are James Cammack on bass and Idris Muhammad (a personal favorite, nice to see him here, too) on drums. Jamal is aggressive and often angular, and his style shouldn't be a stretch for fans of more overtly experimental pianists like Cecil Taylor. O.C. Williams joins Jamal for the beautiful "Whisperings," the album's sole vocal spot and another opportunity for Jamal to stretch out his dynamic approach to the keyboard. And by the way, the liner says that Jamal's hat was designed by Ishmullah's Famous Hats of Oakland, California. Too bad Monk wasn't around long enough to endorse men's haberdashery.

Wednesday, September 4, 2013

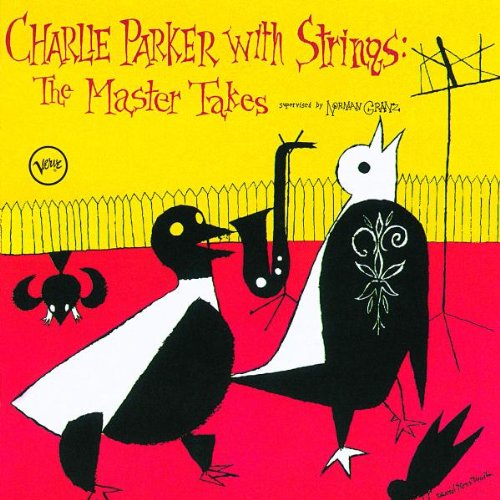

130. Charlie Parker / Charlie Parker with Strings: The Master Takes (1995)

If you're only interested in Bird's famous recordings with a small orchestra, then you can save a little coin with this attractive disc. (It's only fair to say that for just a few extra bucks, $20 on average for used, you can have all the material here plus much more and better liner notes if you buy the Complete Verve Masters.) But as this disc's title indicates, it contains the complete master takes of Bird's famous 1950 sessions with strings. In addition to the 14 tracks contained on the original two LPs by Mercury, the Verve CD contains 10 bonus tracks recorded 1947-1952. The orchestral numbers are all standards, and when they work, it's magic. Some have argued that this was a commercial sell out. It was so successful that it led to a flood of other artists playing with strings. The truth is that Parker himself always wanted to play with an orchestra, and these recordings fulfilled his dream. In the greater context of jazz today, I think it's a stale argument and intentions don't matter. Who cares whose idea it was? Hey, it's Bird, there's some extra musicians, and the result is warm, elegant, and hard to turn off. Whoever can't enjoy such an engagement must be difficult to please. Likewise are my feelings for Cliff Brown, Dizzy, or anybody else who went in the studio with an orchestra in the 1950s.

Labels:

1947,

1948,

1949,

1950,

1951,

1952,

bebop,

bop,

charlie parker,

charlie parker with strings the complete master takes,

mercury,

orchestra,

review,

tenor sax,

tenor saxophone,

verve

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)