Recent listening, current

Archived listening, 2013-2016

Tuesday, May 28, 2013

109. Julie London / Julie is Her Name (1955)

Julie London's range and the timbre of her voice is one that sits very well with me. Ensconced within her silky mezzo soprano is a space filled with sumptuous partials and overtones that make a single note sound like a chord. Her voice and my wife's are quite similar so when I listen, I sense something familiar. In the classic debut Julie is Her Name, London's young voice is the main attraction and backed often by only a guitar. Her phrasing and timing leave you on the edge of your seat, wondering where the next phrase will fall ("It Never Entered My Mind"). She's always playing this way with the lyrics and her timing, while Barney Kessel anxiously holds back comping. Later in her career, she fronted a big band whose eloquence and power gave her smoldering vocals and lovelorn ballads some extra emotional impact. But here it's all Julie. The album opens with the quintessential "Cry Me a River," and moves through 12 other standards and ballads including aforementioned, quirky "It Never Entered My Mind," and the beautiful "Laura." There's also a second volume, which is just as bit as this first volume, two records that should be on every jazz lovers shelf.

Monday, May 27, 2013

108. Duke Ellington / On the Road with Duke Ellington (1967)

On the Road is a documentary film from 1967 by Robert Drew. For an artist so prolific, Duke left behind precious few film documentaries. There is music performed in the film that'll give you goosebumps but the subject isn't the music itself, it's Duke and how he lives and works. The picture is grainy and saturated like an old Super 8, the audio is muddy, and you'll instantly disregard that because from the outset, you're aware that this is the best film on Duke Ellington that there is. It's delicious, for a Duke fan like me. The camera follows him in his daily routine as he opens his mail, lingers too long backstage on the piano, composes a new tune, or has his breakfast -- hot water, steak and potato, the same breakfast he's had for 40 years. Duke is a funny, funny guy. He's an autocratic employer, an eloquent speaker, and madly devoted to his craft. You see him flirting with fans at the airport, or backstage having a natter with Louis Armstrong, just talking like two old friends, which is extremely interesting. The bottom line is that Duke Ellington runs the show whether it's on the road, at home, or accepting an honorary doctorate. He works all nighters while he's not performing and performs when he's not working. At one point, he tells the crew that he can't imagine what retirement means because stagnation will not look good on him. And it's true, he worked until his death six years later. I think I learned that if I truly want what I think I want, then I know I'm not working hard enough. Like a thunderstorm, the power, sophistication, and beauty of Duke's orchestras always excited and impressed me. Watching it happen in the making reinforced that notion.

Sunday, May 26, 2013

107. Desmond, Brubeck, Van Kriedt / Reunion (1957)

This meeting of the minds that have met before on many occasions is as relaxed as it is concise. David Van Kriedt was the tenor and collaborator in the Octet alongside Brubeck and Desmond. He continued into academia, also playing with Stan Kenton, while Brubeck and Desmond became performers. On Reunion, there are some tastes of the fugue style writing for which the Octet was famous (Bach's "Chorale," the only tune without a Van K. credit), although in the mood is, as I mentioned, quite a bit more relaxed than it was in the Octet. Back then, as the record shows, everyone seemed scrambling to out-do his last chorus. This time, while it sometimes sounds as if there's no clear leader, each man gets a fair share of time during improvisations and the music has the feel of care and balance. The group idea of musicality is very strong. Brubeck often picks up where Van Kriedt leaves off, or Desmond does, with occasional episodes that quote slyly from whatever is near at hand. It's soft, sophisticated music with occasional fireworks ("Shouts," listen for the Brubeck boulder that spins Desmond into a tizzy) and superb arrangements by Van Kriedt, like the sumptuous "Prelude." Van Kriedt's tone is smooth and full like Lester Young, and the timbre is the ideal mixer for Desmond's alto.

Saturday, May 25, 2013

106. Frank Zappa / Hot Rats (1969)

Fusion, like the avant-garde, is a thing that everyone approaches from a different angle. Hot Rats is way off the typical fusion track, if you follow the example set by those who left Miles Davis' electric groups. But Frank wasn't moving in those circles. When he made Hot Rats, as ever, he was following his own muse. On the surface, Hot Rats takes the path of a hard rock band, emphasizing the "rock" half of the jazz-rock equation. It is filled out with intricate arrangements played on various reeds, electric guitar, electric violin, percussion, and keyboards. Most of the solos are blues-based guitar workouts or feedback-laden electric violin riffing by Sugarcane Harris (see "Willie the Pimp," "Gumbo Variations"). On the other hand, it also features quirky, composed pieces whose tight arrangements are closer to a synthesis of jazz and classical elements than they are to any mainstream American rock and roll from 1970. Listeners of European experimental music from the same time period, or Rock in Opposition groups like Henry Cow should have no trouble appreciating such pieces. "It Must Be a Camel" and "Peaches En Regalia" are notable in this regard, likewise the horn charts for "Son of Mr. Green Genes," which remained a live staple for years to come. Zappa was also a DIY innovator in the studio. If he didn't have the equipment he wanted, then he invented it, and he was endlessly creative at the mixing desk. So the aurally warm texture of Hot Rats was created with a forest of meticulous overdubs and tape manipulation techniques that Zappa pioneered on his own. Are you new to Frank Zappa? Hot Rats is a good entry point due to its presentation of several characteristics common to many pieces in the FZ oeuvre. It's also very good for rock audiences and toe dippers because it is listenable, contains none of Zappa's lyrics (which range from funny, to off-putting, to complete bullshit, depending on how they strike you), and is also widely available on CD format.

Labels:

1969,

frank zappa,

fusion,

guitar,

hot rats,

ian underwood,

jazz rock fusion,

jean-luc ponty,

john guerin,

max bennett,

paul humphrey,

reprise,

ron selico,

shuggie otis,

sugarcane harris,

violin

Friday, May 24, 2013

105. Benny Golson / Groovin' with Golson (1959)

Golson only has a single composing credit on this album ("My Blues House"), which is too bad considering how much I enjoy his style of jazz. But that tune, a slow blues, is the very first one on Groovin'. It is adequately seasoned with Curtis Fuller's flashy statements on trombone, perhaps more than Golson himself. Things move to a mid tempo piece "Drum Boogie" that swings hard with Art Blakey at the helm, before cooling down with the Rodgers and Hart standard "I Didn't Know what Time it was." Golson's sax blends sweetly with Fuller's trombone, and both are accomplished soloists. It's nice to hear their tones in opposition, too, as in "The Stroller" where a caustic Golson veritably peels the paint off the walls before we hear Fuller's punchy but softer sounding approach with short, staccato phrases. There's some brilliant piano work by Ray Bryant, possibly overshadowed by Golson or Fuller but easily underrated. Chambers and Blakey get a turn before everyone does fours and the thing wraps up. The quiet "Yesterdays" finishes the album with a whisper. Groovin' was recorded immediately before the formation of the Jazztet, but it's easy to see where things were going. I think here, Blakey gives a hard edge that was missing from even the Jazztet's most brilliant moments.

Thursday, May 23, 2013

104. Clifford Brown & Max Roach / Study in Brown (1955)

Study in Brown is a really enjoyable record. What's memorable, to me, in this Brown-Roach date from 1955, isn't just Brown's exceptional talent on the trumpet, but his talent as composer ("Sandu" is here) and contributions of tenor Harold Land on the front line. Between their instrumental abilities and composed works, the band is a really good combination. A bit like the Cookbook series by Eddie Davis, Brown and Roach went in the studio a few times and each time, the chemistry cooked something special. This set runs from blues to bop to standards, and through a variety of tempos. In the opening "Cherokee," Land can match Brown phrase for phrase at breakneck speed, and the wailing fragility of his reed provides additional texture and urgency. In each tune, Roach gets a lot of room, naturally, carving out his niche in jazz percussion with driving, melodically inspired solos on snares and toms. "Take the 'A' Train" has a really cool introduction and arrangement, and the jaunty "Gerkin for Perkin" keeps it interesting with a cool stop/start rhythm that causes Roach to kick up some dust. Such freshness, vibrancy and joy flows from this recording. It's almost hard to listen and not be overwhelmed by the sad feeling of knowing that Brown would be gone in less than a year.

Wednesday, May 22, 2013

103. Art Farmer / Meet the Jazztet (1960)

I love this album. Art Farmer's Jazztet was a lot like the Jazz Messengers. Their music had a different flavor than the Messengers but each group was stacked with the fine and innovative musicians and each played the picture of hard bop. Benny Golson does the arrangements and the band plays two of his tunes: "I Remember Clifford," the beautiful tribute for which words are woefully inadequate, and "Blues March," an attention-grabbing blues with a startling cadence and spunky arrangement. There are some obligatory standards ("It's Alright with Me," and swanky "It Ain't Necessarily So") during which the band displays its chops like fine silver. Golson and Farmer make ideal foils by themselves, Golson with superheated explosions of verbosity and Farmer with his carefully crafted and natural lyricism. But you can't forget or ignore the contributions of Curtis Fuller, either. He has some really hip parts, with big, brassy punctuation marks or deftly fingered runs that will make you think he's got a cornet. There's mucho variety, the arrangements keep it fresh, and Lex Humphries swings it hard. If you're getting into this type of music, Meet the Jazztet is essential listening.

Tuesday, May 21, 2013

102. Anthology of Big Band Swing, 1930-1955 (1993)

The scope of this Decca Records compilation encompasses the whole swing era from the stomping greats of 1930 to the final holdouts of the mid '50s. The restored sound quality is excellent but the strength, or allure, of this two-disc set is the variety of material that was chosen. The editors did a great job selecting the tracks, a sure success. Their work provides a detailed and meaningful cross section of the many diverse bands playing swing music in the United States. They could have flubbed it. Decca's roster was about as deep as the Yankees bullpen, but it also had some of the biggest guys in it. So in other words, while Basie, Duke, and Benny are represented here, they're not disproportionately represented to the exclusion of the label's other, smaller acts. Instead, the spotlight spreads a little

wider. The resulting collection is presented chronologically and allows listeners to follow swing as it matured and developed over a cool quarter-century. Across 40 tracks, there are 37 different bands that will jump, jive and wail you into a frenzy. There are so many great bands here in one collection, not to mention their soloists -- Fletcher Henderson, Don Redman, Chick Webb, Jimmy Lunceford, Mills Blue Rhythm Band, Tiny Bradshaw, Jack Teagarden, Noble Sissle, Glenn Miller. And the list goes on, and on, and on! I listen to the whole thing and I get excited thinking about the era, the big dance halls and the excitement this type of music provided to people like my grandparents in such a trying time of depression, war, and uncertainty. It's difficult and expensive for a listener to take in all the swing groups one-by-one and try to put them in context. These 40 songs make it much easier to understand foundational jazz music of the '30s, '40s, and '50s. This should be on every jazz collector's shelf.

Saturday, May 18, 2013

101. Buddy Tate / The Texas Twister (1975)

Tate was with Basie in the early days but has many dates to his own name and was a leader whose career lasted well into the '90s. His sound on The Texas Twister is large and assured, with occasional wailing outbursts, but it's less assertive than some other horns associated with the Count, like Eddie Davis or Illinois Jacquet. And I like that, too. But the music on Twister swings close to the Basie band in more ways than

one. To start with, there's the addition of Paul Quinchette on tenor. The first number "The Texas Twister" is an uptempo 32-bar intro

to the proceedings that showcases both horns (Tate on the left,

Quinchette on the right), and has game piano work by Cliff Smalls. I thought it could easily go a few more rounds but the leaders opted to be concise and it's off to the next tune once the front line gets back to the head. Further in the Basie vein of blues-based small group swing, we also get Tate singing a la Jimmy Rushing in several cuts, including two installments of "Take Me Back Baby" that showcase Tate's sweet vocal and the impact of opposed horns. The arrangements feature some expected dueling, a mature and more relaxed but no less exciting form of the stylistic counterpoint from the old days. It happens between Tate and Cliff Smalls, too, as in "Talk of the Town." Tate opens the tune in a whispering voice that is soon hammered by Smalls' angular piano statements directly on top of the beat. Tate returns to state his piece every bit as eloquently and reserved as before, endowing the ballad with some very poignant sensibilities. Tate also plays clarinet, on "Chicago" and the closer "Gee Baby," adding further depth to the quintet. It's a good session and thoroughly enjoyable listen with a few hidden surprises.

Labels:

1975,

blues,

buddy tate,

cliff smalls,

jackie williams,

jazz,

major holley,

new world,

paul quinchette,

quintet,

review,

rhythm and blues,

swing,

the texas twister,

vocal,

vocalist

Saturday, May 11, 2013

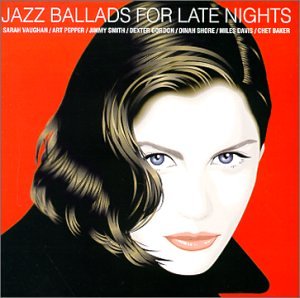

100. Various Artists / Jazz Ballads for Late Nights (2000)

In spite of similar thematic content, ballad comps are not often interchangeable. Each one has a different character depending on who's on it and what tunes they do. You could almost divide them into subcategories of microthemes. Take Sinatra's No One Cares or Chet Baker's Chet, and it's easy to see. Would you play the Sinatra record for a date? Never. Yet Chet could be perfect for a romantic occasion, and in another way, its stormy introspection also suits a party of one. Jazz Ballads for Late Nights has a mood that's suitable for two and seems made that way. It begins with the profound and majestic occasion of Sarah Vaughan singing her blues in "Round Midnight," but the rest of the disc has a warm atmosphere that leans the way of love shared, rather than love lost or unrequited. There is a sly, almost playful "Willow Weep for Me" by the Three Sounds, and also a swank "Lover Man" by Jimmy Smith, with beautiful and rhythmically provocative alto work by Lou Donaldson. Several vocals even the pace, reminding you and that special someone why you're listening (Baker's quaint and pining "My Ideal," or Dinah Shore's "My Melancholy Baby"). I think the mood on the Baker tune should have closed it out, preceded by Ike Quebec, and not the other way around. Baker veritably whispers the closing statements and makes it the perfect song to end on, and it doesn't leave you keyed up the way Ike's impassioned soloing does. But these are mere quibbles. What more do you need? Short answer: a babysitter.

Friday, May 10, 2013

99. John Zorn / Spy vs. Spy (1989)

I remember it clearly. It was December of the year I turned 17, incidentally just a few weeks after I bought The Shape of Jazz to Come, my first Ornette Coleman album. I was in the parking lot of a concert, standing atop my cooler. I had been up there for about 30 minutes or so watching people walk by when one of the guys camping next to us started playing Spy vs. Spy on his car stereo. I had already made myself intimately familiar with the strains on Shape, so Zorn's mysterious and new (to me) spin on "Chronology" was a revelation. It literally fell out of the sky. Once the initial confusion subsided, there was bliss. I stayed on top of the cooler and talked to the guy who put on the album (Nate, from Columbus, who was standing on the ground). We chatted about other Ornette Coleman albums I should buy as we listened to Zorn's elite posse of contemporary jazzists sail through 15 more tunes. Although "Chronology" was the only one I knew, and it was over pretty fast, the rest of the disc already seemed like an old friend. Over the years, Shape and Spy became like mutual codexes to each other, which is funny, considering the lack of material that is common to both. In 1999 I lacked the listening background to bring a truly appreciative context to either record, but I'm astonished that either record filled the hole that it did, and I still enjoy them both greatly and they continually offer me new ideas to invest in.

That is, I think, a testament to the enduring vision of each. That's a mouthful but I can't think of any other way to put it. When I hear Zorn, Joey Baron, Tim Berne, Mark Dresser and Michael Vatcher painting the walls with a group improv like those found on Spy, I can hear their interpretations peeling back the layers of the onion, while simultaneously putting more back on the top. There's so much going on -- the clashing tonalities and meters, the timbres and partials of altos' upper register, the fury of it all. The language of each improvisation is so unique. It's like lightning in a bottle. And yet in all its abrasive, assertive, uncompromising glory, it exudes an inescapable beauty. I like "C & D," "Broadway Blues," "Feet Music," or "Zig Zag" the best, but this is one album I must always start from the beginning.

|

| Somewhere above, I listen to John Zorn |

Labels:

1989,

avant-garde,

elektra musician,

free jazz,

group improvisation,

joey baron,

john zorn,

mark dresser,

michael vatcher,

ornette coleman,

punk jazz,

quartet,

spy vs spy,

thrash jazz,

tim berne

Sunday, May 5, 2013

Current interests and other things.

Being pinched for time hasn't killed my jazz habit, it's just changed the way I do it. It's certainly changed the way I write about it. If you're paying attention, you know I'm currently four days behind the 8-ball. I'd like to think I'm about to come up to speed in this and a few other projects, but who knows. The last four weeks have been very busy for me and the next four promise to be even busier. Hard work is a good thing.

I've been stretching out a little bit, exploring dusty corners for new things I haven't listened to. I look forward to blogging more about Rez Abbasi, Nathan Davis, Esperanza Spaulding, Stanley Turrentine, Ted Nash, and Rabih Abou Khalil.

Dig that camel.

I've been stretching out a little bit, exploring dusty corners for new things I haven't listened to. I look forward to blogging more about Rez Abbasi, Nathan Davis, Esperanza Spaulding, Stanley Turrentine, Ted Nash, and Rabih Abou Khalil.

Dig that camel.

Wednesday, May 1, 2013

98. John Coltrane / Interstellar Space (1974)

This was actually recorded in 1967, but not released by Impulse! until '74, almost a decade after Coltrane's death. It's famously dense, but not impenetrable. Throughout the album, Coltrane demonstrates a litany of technical ideas by running through scales, stacking chords, and changing meters in snatches of modal improvisation. It is very experimental and obviously one of the more inaccessible works in the Coltrane canon. Interstellar Space was recorded shortly after the session that produced Stellar Regions, so many of these pieces share themes. "Saturn" is the longest piece, also the only one to lack bells in the intro. Some people latch onto "Venus" which is the closest thing to a conventional melody on the record. Rashied Ali plays like a mystic, and I often find myself listening to him more than Coltrane, whose explorations are searching but also noisy and make the ear weary. Ali's rhythms seem to accommodate any of Coltrane's fancies, or rather Coltrane is free to step in and out of them when it suits he is doing. This is huge music for 1967 that has been hotly debated, put down, or academically dissected ad nausea ever since. I'm happy that the package was expanded on CD to include the similarly minded "Leo" and "Jupiter Variation." 2013 has a lot more context for this type of musical activity than there was in 1967, and it's found a happy home with hundreds of people. That's the crime of being ahead of your time, that it takes everyone else that much lonegr to catch up. Gregg Bendian chose this album to recreate with Nels Cline (Interstellar Space Revisited), describing it in the liner as his love letter to free jazz drumming. In that regard, I can't think of a finer template. Listen to both, see where it takes you.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)