Recent listening, current

Archived listening, 2013-2016

Showing posts with label album. Show all posts

Showing posts with label album. Show all posts

Wednesday, March 6, 2013

52. Gerry Mulligan Meets Johnny Hodges (1959)

Once upon a time, Verve (and the other labels, too) did a handful of records where one player "meets" another. These albums are like fantasy baseball for jazz. Some are really good, while others start and finish without really accomplishing anything. This time it clicks. Together, Mulligan and Hodges do a smooth and balanced set comprised of six originals, three from each. On Side 1, Mulligan's "Bunny" and the self-descriptive "What's the Rush?" set the mood, before moving into the swank, bluesy territory of Hodges' "Back Beat" and "What It's All About." Claude Williamson, Buddy Clark and Mel Lewis are the rhythm section, and are good at keying in on what the leaders are doing. Sonically, the saxes are a sweet blend with Claude Williamson and the carefully considered bass lines of Buddy Clark. When Mulligan and Hodges take choruses, the one will start developing where the other left off. There's no requirement for this, it's just good artistry. So instead of going in two personal directions with the rhythm section plodding in tow, Mulligan and Hodges make the album a cohesive and jointly constructed product. No surprises musically speaking, nothing groundbreaking, no one trying to bring down the roof. But does there need to be? It's just really good jazz from five great musicians.

Tuesday, March 5, 2013

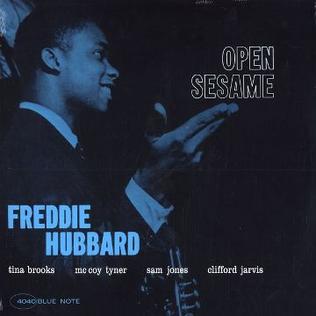

51. Freddie Hubbard / Open Sesame (1960)

I think: Open Sesame. The title says, as if by magic, Freddie

Hubbard has arrived. It's is a very strong debut and an easy mark for

the core collection. We also get a great band. Tina Brooks on tenor really tears it up. On the title track, Brooks sinks his teeth into the riffs, blowing these long, stretchy phrases that step across the bars like hurdles and land back in time when he runs out of breath. He's a good man on ballads, too, like the droopy "But Beautiful." Behind the traps is Clifford Jarvis, two years shy of becoming a Saturnian. His energy, polyrhythmical claptrap and close work with Hubbard's improvisations add depth that is a few cuts above the standard hard bop set. Sam Jones plays big round notes in a sentimental and melodic style which at times reminds me of Ray Brown. He's aided everywhere by McCoy Tyner's drizzling fills and colorfully voiced chords. "Gypsy Blue" has a Latin tinge. The head has a cool arrangement where Hubbard and Brooks play in, and then slightly out of phase, hypnotically swinging it along. Hubbard's centerpiece is the rollicking "All or Nothing at All," where he shows off his chops in wild, flashy runs, rubber fingered flourishes, and big brassy blasts in the upper register. The guy's a natural who learned to improvise before he learned to read, and it shows.

Sunday, February 24, 2013

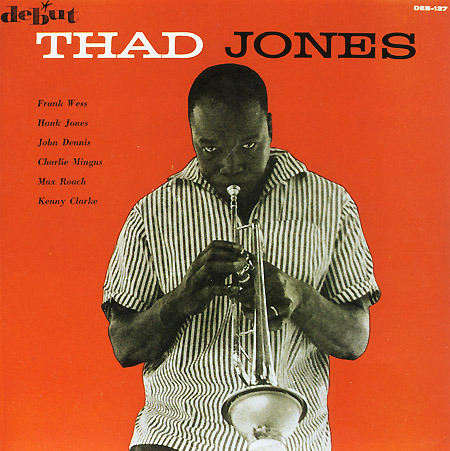

43. Thad Jones / The Fabulous Thad Jones (1958)

This LP is collated from two sessions recorded by Rudy Van Gelder in 1954 and 1955. Group 1 is Jones, Charles Mingus, John Dennis and Max Roach. Although Jones leads the session, it feels strongly like Mingus is at the helm. The group is rhythmcally direct, playing a mixture of standards and Thad Jones originals. The spotlight is on Jones for every track, although "I Can't Get Started" stretches out with some interesting interplay between Jones and Mingus, and has tempo changes that lean the way Miles Davis did with his "Basin Street Blues." Jones plays evocatively with and without a mute, and shows off a only a little bit. Group 2 is Jones, Mingus, Hank Jones, Kenny Clarke, and the tenor sax and flute of Frank Wess (a la Hank Jones with Frank Wess). It's a somewhat softer, lush and casual small-group swing that excels in the ballads. This band sounds gelled and confident due to the players' associations in the Basie band. Together, the two bands make a good album that doesn't sound disjointed or uneven, although their differences are plain.

Labels:

1954,

1958,

album,

charles mingus,

cornet,

debut,

fantasy,

frank wess,

hank jones,

jazz,

john dennis,

kenny clarke,

max roach,

review,

thad jones,

trumpet

Saturday, February 23, 2013

42. Lester Young with the Oscar Peterson Trio (1952)

For the most part, this disc is all about Lester, who performs admirably but is noticeably shakier and lacks that bright, bursting energy he exhibited a few years earlier. He frequents the lower register in soft, emotionally inflected lines that give the ballads a uniquely personal treatment. It's unmistakably Lester on every track and there is some very keen playing ("I'm Confessin' (That I Love You)" is just one example, or a close approximation of the man we once knew in "Just You, Just Me") but in other places I hear him struggle with timing and the impact of the inventiveness is lost. The dramatic ascents and nose dives he used to do so well seem to sputter like an injured bird, rather than a stunt pilot. Young usually takes the first chorus, and sometimes afterwards I swear I can hear Peterson and Kessel emulating his style on their instruments, playing several "even" bars before throwing the rhythmic weight of the next phrase off to one side and rushing in after it. Even if he isn't in the same form as the recordings from 1946-1949, he's still Lester Young and when it works, it's untouchable.

Sunday, February 17, 2013

37. Duke Ellington / Ellington Uptown (1952)

It seems like Ellington Uptown gets short shrift, which could put off a listener who hasn't heard it. It really needs another look because it's an excellent album, and the orchestration and arrangements are especially good. Duke's work is like pizza: when it's good it's great and when it's bad... well, was it ever bad? Be honest. Even when it wasn't that great, it was still better than most everything else. By comparison, I think some of Duke's legacy is unfairly praised. All the "three minute masterpieces" are cracking good sides, but they're not all on the same level, and so the mediocre ones are elevated to a higher status partly by association and partly by critics who haven't listened to them all. Yet Duke's work from the 1950's languishes in the shadows, right at the moment when his famous soloists had matured and were really hitting a stride. With that in mind, this set swings really hard and practically lifts you off the floor. The arrangements are the full-length concert arrangements, closer to what the band was doing on stage rather than something they cooked up just for the record. There's even a live cut ("Skin Deep") with a famous drum solo by Louie Bellson. My favorite moment, on an album filled with favorite moments, is listening to Betty Roche sing "Take the 'A' Train." She had such a fun and playful style, like improvising a scat vocal that self consciously stabs at bebop. I love it when she sings her last line and leans off the microphone as the massed band blows in behind her. It sounds like the girl is falling backwards into an approaching tidal wave. So enjoy these chestnuts, which may be another example of Duke reinterpreting his back catalog, but are also a darned good example of what this band was all about.

Labels:

1952,

album,

betty roche,

big band,

duke ellington,

ellington uptown,

jazz,

piano,

review,

swing,

vocal,

vocalist

Saturday, February 16, 2013

36. Henry Threadgill Sextett / Rag, Bush and All (1989)

Mr. Threadgill turns his attention to the possibilities of composing for a jazz sextet, laying aside his penchant for world percussion and other unconventional orchestration. There aren't any frame drums and you won't find an oud, but between Threadgill's bass flute, the bass trombone (Bill Lowe's sole obligation), string bass, cello, and flugelhorn, the instrumental colors are focused in the lower ranges. Add two drummers and shake, and the recipe really works -- bright splashes from Threadgill's alto and Ted Daniels' cornet create a high flavor that is joined by Diedre Murry, whose free explorations on the cello wouldn't sound out of place with Henry Cow. Fred Hopkins, no stranger to interplay with Murry or Threadgill, was always a creative improviser, and uses the full range of the instrument, playing so percussively that you'd think he was a percussionist himself. Threadgill's abilities as composer and arranger are ever apparent, playfully alternating between snatches of melody and bumpy sections of turbulent rhythmic counterpoint. When the soloists open up in later sections of "The Devil is on the Loose and Dancin' with a Monkey," maybe it's the horn and twin drummers, but the music feels a smidge like that of the second Miles Davis Quintet. And in the sections surrounding Threadgill's chorus in "Sweet Holy Rag," the

drums and winds play slightly out of phase and recall effect of the opening track on

Davis' Nefertiti, that of an unsettling and self-propelled whole that creeps along like a caterpillar and demands the ear's attention. During collective improvisations, the musicians have their ears wide open, and the product is a busy and tantalizing melee of interwoven phrases and meters that step above one person simply jumping into line behind the next. "Gift" is the shortest piece on the record, a beautifully dirge-like spell of bowed strings, chimes, and arranged winds that is overshadowed by the 12-minute tempests on either side of it. Yet again I listen to an album like this one with such interesting compositions and wish it was available to new generations of jazz composers and musicians, but shake my head in awe of the fact that it has lapsed out of print. There are numerous groups in modern jazz that could adapt these tunes nicely.

Friday, February 15, 2013

35. Stanley Turrentine / Look Out! (1960)

Look Out! is a good title, and the set list is what first jumped out at me. Sandwiched between Turrentine originals like the title track and "Little Sheri" are contemporary jazz compositions and covers that don't get around much. For instance, "Tiny Capers" is a nice one by the much missed Clifford Brown, and "Journey into Melody" is an offbeat selection by the prolific movie score composer Robert Farnon. Regarding the latter, I've never heard anyone else ever cover it. In a jazz album, I like that kind of variety and Turrentine's focus on melodic variation and a soulful technique give it plenty of lift. He's not alone -- Turrentine veteran Al Harewood really swings on the hi hat and hard stick rolls, sounding much like he did with Art Farmer and Gigi Gryce a few years earlier, but coolly and thoughtfully adapted to the particular demands of Turrentine's hybrid of hard bop and the emerging soul jazz. It's a straight ahead session, one of the best of the year on Blue Note and the reissue deserves a second look. Oh! I nearly forgot: they call Turrentine the Silver Flash, and you've got to love that.

Thursday, February 14, 2013

34. Milt Jackson & John Coltrane / Bags and Trane (1961)

Released after My Favorite Things, Giant Steps, and Coltrane Jazz, this collaboration was recorded in 1959, and was actually the first album to be recorded by Coltrane on his new contract with Atlantic. It was sensible to wait until '61 to release it. Because while it's very good music, blues and standards by a quintet, and the exchange of ideas between Trane and Bags during improvisations makes it a few cuts above what it could be, given their prior associations, this album doesn't make the same splash. He wasn't their guy anymore, so you could view it as a safe play for Atlantic while Coltrane was en route to Impulse. I don't understand why Atlantic altered the sequence of the original LP when they released the CD, but they did. In this case, I don't think it matters. The Bags-penned blues numbers like "Late Late Blues" and "Blues Legacy" are my favorites. It seems that no matter where they were in the music, the blues were never very far behind either player, and that's a good thing.

Labels:

1959,

1961,

album,

atlantic,

bags,

bags and trane,

blues,

john coltrane,

milt jackson,

milt jackson and john coltrane,

prestige,

quintet,

tenor sax,

tenor saxophone,

trane,

vibes,

vibraphone

Wednesday, February 13, 2013

33. The Dave Brubeck Quartet / Jazz: Red Hot and Cool (1955)

Recorded live at New York's Basin Street club across three nights, this quartet isn't the same one that gelled on "Take Five," but the Joe Dodge/Bob Bates team sounds fine and contributes to the Brubeck formula admirably with rhythmical inspiration and some interesting polyrhythmic steering from Dodge. The pieces for the Morello-Wright band are already in place, like polytonality, polyrhythm and fugue-like structures. But these were already present during the days of the Dave Brubeck Octet, and earlier still during formative late nights at the Blackhawk. So if you're into Brubeck then there's plenty of good music here to enjoy. Sonny Rollins is credited in the notes of Saxophone Colossus for being the first jazz musician to develop his improvisations with an ear toward their musicality, as spontaneous compositions. That makes sense if Ira Gitler wasn't looking at the West Coast where Brubeck was doing exactly that. Full shifts in signatures mid tune, Desmond responding on the fly to Brubeck's harmonic cues -- as Brubeck's groups ever were, interesting music that rewards deep listening.

Tuesday, February 12, 2013

32. The Jimmy Giuffre 3 / The Easy Way (1959)

The Easy Way is darned sneaky, the way it passes so quietly upon first listening. The music is so sparse that it stops your breath like a stillborn moment, a feeling almost too sparse, but the second time around, that same quality forces a closer inspection and reveal ongoing relationships of very dynamic interplay at the heart of the chemistry. I keep going back to it. In this 1959 session, Giuffre swaps bassist Ralph Pena for Ray Brown, trading the busy sound of Pena for Brown's commanding and bluesy style. They work with it. On "Ray's Time" we get an extra dose of the Ray dimension while Jim Hall comps and Giuffre lays out. When Giuffre is playing he is taking a lot of ideas from Brown and Hall, who turn them right back around. The album is divided into two distinct halves: the first comprised of blues like the Ray tune and standards like "Mack the Knife," and a more exploratory or section, marked by "Time Enough," "Montage," and "Off Center."

Labels:

1959,

album,

cool,

jazz,

jim hall,

jimmy guiffre 3,

ray brown,

review,

the easy way,

trio,

verve

Monday, February 11, 2013

31. Wes Montgomery / Boss Guitar (1963)

This is a really slick album by the Wes Montgomery trio, one of four recorded with organist Melvin Rhyne. Montgomery takes most of the leads, although Rhyne does get a few. When he does, he doesn't use the draw bars much, although he plays a great bass accompaniment on the pedals and occasionally uses the bars while interplaying with Jimmy Cobb or comping. So it's pretty much Wes Montgomery, right up front, all the time. Most of the tunes are standards except for two. It's accessible music of the funky and soulful variety that Wes purveyed across his career. The music is so smooth that it's almost easy to ignore if Montgomery wasn't so good, and Jimmy Cobb certainly keeps listeners awake on the drum kit. He does the octave picking a little bit, but does more blues-based riffing and plays some very spontaneous figures in the upper register that remind me of alto saxophone technique. "Besame Mucho" is the standout mark of a seasoned professional and Montgomery's own "The Trick Bag" really heats up. From the looks of things, I think Rhyne and Cobb like "Trick Bag," too.

Labels:

1963,

album,

blues,

boss guitar,

guitar,

jazz,

jimmy cobb,

melvin rhyne,

organ,

review,

riverside,

soul jazz,

trio,

wes montgomery

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)