Recent listening, current

Archived listening, 2013-2016

Showing posts with label 1963. Show all posts

Showing posts with label 1963. Show all posts

Saturday, July 6, 2013

112. Paul Desmond / Take Ten (1963)

If you can't get enough of "Take Five," then Take Ten is the album for you. It's one of several excellent slabs made during Desmond's many quartet sessions for RCA Victor. The band is Jim Hall on guitar, a moonlighting Connie Kay on drums and Gene Cherico on bass. Fellow Brubeckian Eugene Wright subs for Cherico on "Take Ten," adding an extra dimension of conceptual continuity to this 10/8 reworking of its famous counterpart. It starts with a familiar vamp that is reminiscent of a studio orchestra trying to avoid paying royalties for the genuine article. But then Desmond starts in on a deep and bluesy riff, finding new territory inside of an old melody. He blows these long and contemplative notes that explore the tonal color of the mode and remind me, in a very limited sense, of later work by Jackie McLean or John Gilmore. It's a treat, especially when he decides to hold on for just a bit longer and sustains the phrase with some vibrato. Proceedings quickly change the course toward Desmond's passion for bossa nova. In spite of an American burnout on the form, Desmond was one of its stalwart practitioners, and originals like "El Prince," "Embarcadero," or "Samba de Orfeu" are fine examples. Kay and Hall give the sessions that extra something it needs. Kay has a nice technique that intertwines his ever present cymbals with a driving attention to the skins. This band gives him elbow room that was impossible in the immaculately executed pieces by MJQ. A normally taciturn Hall takes some interesting breaks mixing chords with short flurries of single notes and a lot of fun riffing, and he is one of my favorite musicians. Together they make a melodically focused disc with good performances and an excited but cool, relaxed vibe that I wholeheartedly recommend. It ends as sweetly as it began, with an uptempo "Out of Nowhere" featuring George Duvivier on bass. The section at the end where Desmond has the floor to himself with punctuation marks by Kay is just magic.

Thursday, June 27, 2013

111. Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus & Max Roach / Money Jungle (1963)

Money Jungle is all about contrasts and individuality. The music is famously, and often physically, tense. The grit is established on the first track "Money Jungle" where Mingus spends much of his time aggressively bending a static harmonic element while Duke assertively pounds big blocks across the registers. Each musician has a distinct playing style, and no one gives an inch for the notion of a group product. Remarkably, a unique group product is exactly what we get. The mood often swings to moments of quiet beauty, but rocks quickly back to outbursts of boulder dropping and more assaults on bass and drums. At times it sounds as if Duke is pointing to sections of his orchestra which are not actually in the studio, playing electrifying chords in his characteristic staccato style before drawing back in contemplation and moving his hands to other registers. With the keyboard laid out in front of him, he's arranging while improvising. A listener with experience with titles in the Duke Ellington catalog will hear the bones of the brass and reeds as sections rise and fall in the imaginary arrangement. I'm happy Duke had the foresight to request making this album with one of his greatest adherents, Charles Mingus, possibly the only talent in jazz that may have been equivocal in terms of composition, orchestration or arrangement.

Saturday, June 22, 2013

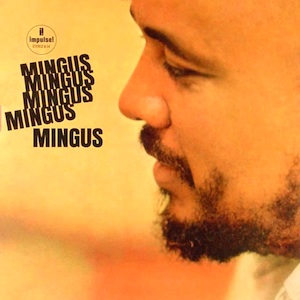

110. Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus (1963)

Mingus, the master orchestrator. Mingus the composer. Mingus the performer. He's got so many credits on this album that I marvel at how it doesn't sound one bit overrun by his presence, yet it's distinctly his product. The music swings with a loose and careening vibrancy that is electrified with spontaneity and invention. With just 10 pieces, his arrangements sound as quiet as a quartet or as powerful as a big band. Its performers lend the air of familiarity, dashing in and out of ensemble jams like "Better Get Hit in Yo' Soul" or blending sublimely as in the steamy rendition of "Mood Indigo." Mingus listeners will immediately sense the presence of old friends, because many of the tracks are new treatments of preexisting Mingus tunes. I'll let you figure what is what. As for soloists, I really enjoy Charlie Mariano (bias alert, I just got Blue Camel so I'm on a bit of a bender) or the shambling Walter Perkins on drums.

Monday, April 29, 2013

96. Eric Dolphy / Conversations (1963)

The first side of this LP contains loosely swinging and glittering interpretations of two tunes ("Jitterbug Waltz" and "Musical Matador") that are, upon first impression, standard enough. But in Dolphy's hands they are things transmuted: multiform, elastic musical caricatures, elating and jubiliant. They are filled with evocative solos by Dolphy and feature tantalizing interplay with his group. Bobby Hutcherson paints the walls with thick chords and his two independently minded mallets seem to dance in circles while Dolphy ambulates on whichever instrument in the foreground. While the second side contains a shade of what colors the first, it is largely a different, darker and more serious, affair. Still rooted deeply in traditional material and reverently anchored to its origins, the music of Side Two seeks progress in the opposite direction. Like Dolphy's solo extemporizing of "Love Me," where his phrases adopt the cadence and tonality of the human voice and the alto literally speaks. In an impassioned conversation between two lovers (I think, but who knows?), he blows figures that invoke the ballad's humanity: blind, animalistic and primal sounds of raw feelings. It is beautiful but also adeptly cerebral, setting the stage for the centerpiece to come, "Alone Together." This is a reaching, expressionistic and inherently modern synthesis of traditional jazz and contemporary art music. Together with The Iron Man (recorded during the same sessions and itself another under-appreciated slab of Dolphy alchemy) the two records play like notecards to Dolphy's thesis presented on Out to Lunch. The final 13-minute piece creeps along just Davis and Dolphy, capriciously turning corners and building up others in its wake, as if trying to lose an unseen pursuer. With the preponderance of university and public radio jazz programs, this octet needs more attention. Airplay, airplay! It's like a Dolphy codex, a smaller, more manageable prototype of the brilliance that was to come.

Labels:

1963,

alto saxophone,

bass clarinet,

bobby hutcherson,

clifford jordan,

conversations,

eddie khan,

eric dolphy,

flute,

fuel,

huey sonny simmons,

jc moses,

octet,

richard davis,

varese sarabande,

william prince lasha

Saturday, March 2, 2013

48. Don Wilkerson / Complete Blue Note Sessions (2001)

A nice release from Blue Note, culling tracks from the four LPs they released for Wilkerson from 1960-63. It's a double disc and the remastered sound is on par with the other excellent Blue Note re-releases. Wilkerson was a tenor who worked with a variety of artists including Ray Charles and Cannonball Adderley (no surprise) and was at home playing blues-based and danceable soul jazz that was easily related to ("Senorita Eula," "Drawin' A Tip,"). With a sophisticated sense of melodic variation and good use of legato dynamics, he steps beyond the prereqs for soul jazz and creates a unique blend that rewards if you listen closely. He's also fond of repeated, motivic phrases that carry the groove. The bands he plays with, especially the combo with Graham Greene, know right where he's at, and turn up the heat when he finishes a chorus. Wilkerson's "San Antonio Rose" (with a cooking solo by Greene) stands out to as a particular good take, so does the interesting "Pigeon Peas" which has me listening a few times over to catch what Wilkerson is doing with the drums. It's fine stuff, top to bottom.

Monday, February 18, 2013

38. Miles Davis / Ballads (1990)

Talk about the quintessential nonessential Miles Davis CD, this is it. Columbia compiled a scanty eight tracks recorded between 1961 and '63, and released them here with a ballads-only theme. Very little about Miles Davis in the sixties sounds dated or anachronistic to my ears, but in today's climate of iPods and customized playlists, such a compilation album doesn't have the same role it did in 1990. And this product, as a whole, hasn't aged well even if the opposite is true for the selections themselves. I say it didn't age well but I'm not sure it would have made sense 20 years ago, either. First, it's an odd choice of material if you're trying to showcase what Davis could do with a ballad. Five tracks by the Gil Evans orchestra, two by the quintet with George Coleman and a live cut by the Mobley quintet is a rather baffling sequence. Are we doing Evans, or a club date? Because the two are so unlike each other that the program seems interrupted when the group changes. The very context of the Gil Evans orchestra was so different than that of a street group, any street group, that a ballad within its fold is a thing transmuted, a wholly different musical animal. Good work from everyone involved musically, but shame on Columbia for ever selling this.

Labels:

1961,

1962,

1963,

1990,

ballad,

ballads,

columbia,

compilation,

cornet,

george coleman,

gil evans,

hank mobley,

jazz,

miles davis,

orchestra,

quintet,

trumpet

Monday, February 11, 2013

31. Wes Montgomery / Boss Guitar (1963)

This is a really slick album by the Wes Montgomery trio, one of four recorded with organist Melvin Rhyne. Montgomery takes most of the leads, although Rhyne does get a few. When he does, he doesn't use the draw bars much, although he plays a great bass accompaniment on the pedals and occasionally uses the bars while interplaying with Jimmy Cobb or comping. So it's pretty much Wes Montgomery, right up front, all the time. Most of the tunes are standards except for two. It's accessible music of the funky and soulful variety that Wes purveyed across his career. The music is so smooth that it's almost easy to ignore if Montgomery wasn't so good, and Jimmy Cobb certainly keeps listeners awake on the drum kit. He does the octave picking a little bit, but does more blues-based riffing and plays some very spontaneous figures in the upper register that remind me of alto saxophone technique. "Besame Mucho" is the standout mark of a seasoned professional and Montgomery's own "The Trick Bag" really heats up. From the looks of things, I think Rhyne and Cobb like "Trick Bag," too.

Labels:

1963,

album,

blues,

boss guitar,

guitar,

jazz,

jimmy cobb,

melvin rhyne,

organ,

review,

riverside,

soul jazz,

trio,

wes montgomery

Tuesday, January 15, 2013

04. Kenny Burrell / Midnight Blue (1963)

An album long in the making, according to the liner notes, and by the leader's decision, the selections were limited strictly to the blues. For this reason, I think putting Stanley Turrentine on tenor sax was an especially wise choice. When I listen to Midnight Blue, I'm listening to Turrentine's soulful attack and swinging timing as much as I'm listening to Burrell's guitar. Turrentine aside, there is notable variety in the arrangements, and a few tracks even work to the exclusion of one or more players. I'm impressed with the variety of different moods and textures the Burrell group can coax out of a single musical form, a testament to the power of the blues. Differences in mood between "Chitlins Con Carne," "Gee Baby Ain't I Good to You," and the quietly heartfelt solo voice of "Soul Lament" are simply flooring.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)