Moonflower, released 1977, is a mixture of new studio material and contemporary live performances that demonstrate, in equal measure, all components of the Santana sound. Carlos Santana had spent the previous decade exploring the nuanced corners of this thing he’d invented called “Latin jazz rock fusion.” Of course, we didn’t call it that back then, we were still a few decades away from piegonholing everything into an early grave. The unique music was just the thing that Carlos did. But by the time Moonflower reached audiences, he’d come to the top of the pyramid and was ready to jump off. So the form I’m talking about -- a lysergic combination of free-form acid rock punctuated by Latin dance rhythms of primal intensity, and buoyed by the harmonic message of jazz and slick sensibilities of pop -- as far as I am concerned, was perfected right here. All the other Santana records up to this point demonstrate one of these aspects superbly, but only now are they brought together under a single heading. Such a culmination of style is the reason Moonflower is just so damned good, and why you need to stop whatever it is you’re doing, right now, and listen to it for at least a week, straight.

Santana’s guitar is a sustain bomb, famously so, and it comes in spades on this album. We call it, “neverending sustain” because that’s exactly what it is -- a controlled feedback loop between a guitar pickup and a very loud amplifier, and Carlos basically wrote the book on it: First, crank a tube amp to within a few volts of its life. Then, plug in your guitar and roll its volume knob back to a level that won’t cause a lawsuit. As the notes you play start to fade, roll that volume knob back up to keep them going. Once you hit the sweet spot, just stand there and let the message ring…. forever if you want. In this way, a few well placed strokes of the pick become epic vehicles of self expression, whole chapters in the book of whatever your song is trying to say. At least, that’s how it works if you’re Carlos Santana. During soundchecks, he paces around the stage playing the guitar until he finds the magic distance to stand from the amp, and marks off the spot with duct tape. His amplifier cabinets sit at waist level so the speaker can see the guitar. The whole process is calculated and diabolically simple, but the net effect is packed with an intensity that so belies its simplicity, you’d swear it’s witchcraft. The sound is rapturous bliss, or euphoric jubilation. Otherworldly. It’s a miracle note. It shouldn’t still be there, it should have melted away to silence by now, but there it is. And therein is another component of Santana’s music, amply demonstrated on Moonflower -- the magic-realism of Latin folklore, the power of the supernatural in everything, and the tingling, electric sensation of listening to a really good Santana record.

To get the gist of what I’m saying, turn up the stereo good and loud. Do it in the car, in a parking lot, standing still. Don’t try to drive while appreciating guitar feedback to its fullest capacity for fulfillment. Do it in an armchair with a good pair of flat response cans, or, if no one’s home, open the fader and let the sound blast through your speakers. Moonflower offers high grade sonic transcendence on tap. For the experience of a live concert, listen to the careening beauty of “Black Magic Woman,” “Savor,” or “Soul Sacrifice” from the Abraxas era, complete with Carlos’ signature fuzz and effects, and the raucous, chaotic energy of Chepito Areas on percussion. Songs like “Europa” and “Transcendence” softly (but not quietly) offer the quintessential example of the Carlos Santana Sound in its starkly beautiful phrases and lengthy single-note passages of sustained sound. The latter features a masterpiece solo that you don't want to miss. With a snazzy snap and velvet touch, the subtle hooks of newcomers like “I’ll Be Waiting,” “Zulu,” and “Flor d’Luna” point to the coming years when Santana transitioned to pop and album oriented rock. If Caravanserai is the album that bridges the gap between Santana's acid rock genesis and their more advanced forays into further realms of jazz and progressive rock, then Moonflower is likewise the album that marks where Santana funnels all it learned from the second part of the journey, and strikes off in a new direction once again.

Recent listening, current

Archived listening, 2013-2016

Showing posts with label fusion. Show all posts

Showing posts with label fusion. Show all posts

Monday, July 13, 2020

Friday, February 10, 2017

212. Weather Report / Legendary Live Tapes: 1978-1981 (2016)

On point! Four discs of hitherto unreleased live material from Weather Report's finest lineup. Pastorius recorded a healthy parade of studio LPs with the group and played dozens of gigs. His tenure is my touchstone for the Weather Report discography (I'm a native South Floridian, and admit heavy local partiality). I never saw them live, and I wore out the 8:30 album. That album's cushy overdubs and post-production soften the raw, affirmed talent in evidence on the live document. Given the Report's rep for slick and innovative studio work, I concur and take no issue there. But needless to say I am very happy that these tapes were assembled and released so we can hear them in the buff. Without hitting trading circles for soundboards and audience tapes, it's enough to pore over for a few years. Working through the first disc, my ears perk at Erskine's sparkling and aggressive work behind the drum kit, and his interactions with Jaco. Half the total sound is the rhythm section, hard to believe that only two people are carrying that. Nice notes are also included. While you wait for these to arrive in your mailbox, I heartily recommend the aptly titled Trio of Doom live disc with McLaughlin and Tony Williams.

Saturday, September 17, 2016

210. Santana / Santana III (1971)

In the dictionary next to the word "essential," you'll find a picture of this album. Sandwiched between the seminal Abraxas and the revolutionary Caravanserai, Santana's third LP finds the band now very comfortable inside their invention, that unique fusion of Afro-Cuban rhythm with pan-Latin import and the ferocious, unrelenting pound of a psychedelic rock and roll band in full flight. If you liked Abraxas, don't forget to go the extra step and get this one, too. Because none were doing it in 1971, and none have done it better since. I think it's amazing how fresh and how mature the group sounds for just the third album, and yet, with all the swirling Hammond organ, raucous percussion and abrasive guitar, the thought of Caravanserai's chill embarkation for parts unknown almost brings a tear -- and by the way, I love Caravanserai. Compared to its immediate predecessor in the discography, III is rougher around the edges, a little more relentless in its pursuit of the groove, and maybe even a little less accessible. The music is fully cooked and raging. It sounds a lot like a live album, and the segues between tracks are so tight that they beg you to look for the seams. The audio quality on all available CD editions is stellar, and the "Legacy" edition contains a full live set from July 04, 1971 at the Fillmore West, plus extra studio sessions. Play it loud!

Wednesday, July 15, 2015

207. Stan Getz / Captain Marvel (1972)

Here, we find Getz in good form alongside the boys from Return to Forever. His own notes tell us it was Chick Corea who arranged the date, and most of the music is from his pen. But it is the tenor man from another era who craftily renders the smoothly stated leads that flavor the proceedings -- Stan Getz. He's a melodic monster, and a little like Zoot Sims, just can't seem to put a note wrong. At this point in his career, Getz's tone and the agility of his fingers were still intact, and his technique even thriving. So I hear the overlay of the players' contexts and their respective styles as the key to the session, with Getz relinquishing little of his modern cred, leaving the Corea contingent to provide the updated message. Remember, in 1972, Return to Forever was still newly formed. Miles Davis was active, the impact of fusion was unseen, and it was all still very fresh. Appreciate this disc for its personnel pairings as much as for its place in the later Getz canon. And it's got Tony Williams, reason enough for me to plop down for a listen.

Sunday, June 14, 2015

203. The Jeff Lorber Fusion / Wizard Island (1980)

If you don't listen to jazz, you've probably heard Lorber's music on the Weather Channel while checking your local forecast! The back catalog is a bit more interesting, but not by much. This record was a #1 seller for Arista, and it sounds every bit the part. Cast in the same mold as the heavy hitters like Hancock, Corea, Clarke, et al, it lacks the trailblazing and depth found in those acts (Corea guests on "Rooftops"). Selections are heavy on the funk and Arista Records' special sauce, a superb studio product. It's got a lot of production on it and in spite of the funky corners, some of the songs do take on a two-dimensional pop simplicity. But if you're a fan of good bass playing or vintage synths like Minimoog and the Sequential Circuits Prophet 5, Lorber's album might interest you. I'm not a big fan of soft jazz or heavily produced wallpaper, but I do spin it sometimes. Dennis Bradford and Danny Wilson get high marks for drums and bass, respectively. Bland as this example may be, funky fusion grooves were an entry point for countless musicians of the 70's and early 80's, and Wizard Island does well to show you the ropes.

Labels:

1980,

arista,

chick corea,

danny wilson,

dennis bradford,

funk,

fusion,

jay koder,

jeff lorber,

jeff lorber fusion,

kenny gorelick,

minimoog,

paulinho da costa,

synthesizer,

wizard island

Sunday, May 31, 2015

202. Flying Island / Flying Island (1975)

The self-titled debut from the fruitful but short lived Connecticut group Flying Island has excellent music to offer and deserves wider recognition. Things begin with a sharply executed "Funky Duck," but the material takes interesting turns into weirder territory and more aggressive textures like on "Flying Island" and "I Love to Dance." The music proceeds across shifting time signatures in tradeoffs between Fred Fraioli's electric violin and keyboards by Jeff Bova. Fraioli speaks in squalling, anthemic strokes, sometimes smooth, sometimes menacing, bookended by his fiery runs and escalated, wailing solos. Also present are guitarist Ray Smith, bassist Thom Preli, and drummer Bill Bacon. Smith and Bacon emerge as superb players that make the album much heavier than your typical mid-70s fusion outing. After the violin-keyboard pyrotechnics are over, their work is often the force that distinguishes the band from dozens of similar acts. Flying Island and the follow-up Another Kind of Space should interest fans of higher profile names in '70s fusion like Jean-luc Ponty, Weather Report, or Mahavishnu Orchestra. The musicians are competent and talented, and the total package is professional and well rehearsed. Yet it is not without the spark needed to bring a studio take home for the listener. Highly recommended!

Labels:

1975,

bill bacon,

clavinet,

debut,

electric guitar,

electric piano,

flying island,

fred fraioli,

fusion,

jazz rock fusion,

jeff bova,

organ,

quintet,

ray smith,

review,

sextet,

thom preli,

vanguard,

violin

Monday, May 25, 2015

200. Giger Lenz Marron / Where the Hammer Hangs (1976) & 201. Giger Lenz Marron / Beyond (1977)

Peter Giger's career is full of wild one-way streets. It's like he can do it all, equally at home playing it straight, or rattling through an assortment of percussion instruments in jams of thorny, implacable experimentalism. Where the Hammer Hangs and its sister slab Beyond are just a short stop in his considerable career. Both albums are presently out of print, and are obscure considering his other accomplishments in major jazz circles. If you're familiar with Giger's work in more mainstream engagements, it's probably best to come at these from the Dzyan angle (which was actually my introduction to Giger some time back). Hammer and Beyond were released on his own Någarå label, and stylistically speaking, pick up right where the Dzyan vehicle left off. There are differences. Just like Dzyan, you will hear searching group improvisations, hints of Eastern rhythm and instrumentation, druggy, reverb-laden guitar forays, and plenty of crossover from the above. But Giger Lenz Marron has fewer pedestrian handholds, less that is familiar, and seemingly no rules except for limitations imposed by the instruments themselves. It's like the ingredients of a Dzyan album, but set in a different project removed from whatever restriction was imposed by the group moniker. Although not a major pit stop on the timeline of such prolific musicians as these, the GLM trio interests me for its freedom of form as well as its connections to several trends that first emerged ten years prior. It proves that jazz is a many faceted thing that will continue to be wrought anew by the creative hands and minds that shape it.

Peter Giger's career is full of wild one-way streets. It's like he can do it all, equally at home playing it straight, or rattling through an assortment of percussion instruments in jams of thorny, implacable experimentalism. Where the Hammer Hangs and its sister slab Beyond are just a short stop in his considerable career. Both albums are presently out of print, and are obscure considering his other accomplishments in major jazz circles. If you're familiar with Giger's work in more mainstream engagements, it's probably best to come at these from the Dzyan angle (which was actually my introduction to Giger some time back). Hammer and Beyond were released on his own Någarå label, and stylistically speaking, pick up right where the Dzyan vehicle left off. There are differences. Just like Dzyan, you will hear searching group improvisations, hints of Eastern rhythm and instrumentation, druggy, reverb-laden guitar forays, and plenty of crossover from the above. But Giger Lenz Marron has fewer pedestrian handholds, less that is familiar, and seemingly no rules except for limitations imposed by the instruments themselves. It's like the ingredients of a Dzyan album, but set in a different project removed from whatever restriction was imposed by the group moniker. Although not a major pit stop on the timeline of such prolific musicians as these, the GLM trio interests me for its freedom of form as well as its connections to several trends that first emerged ten years prior. It proves that jazz is a many faceted thing that will continue to be wrought anew by the creative hands and minds that shape it.

Saturday, May 9, 2015

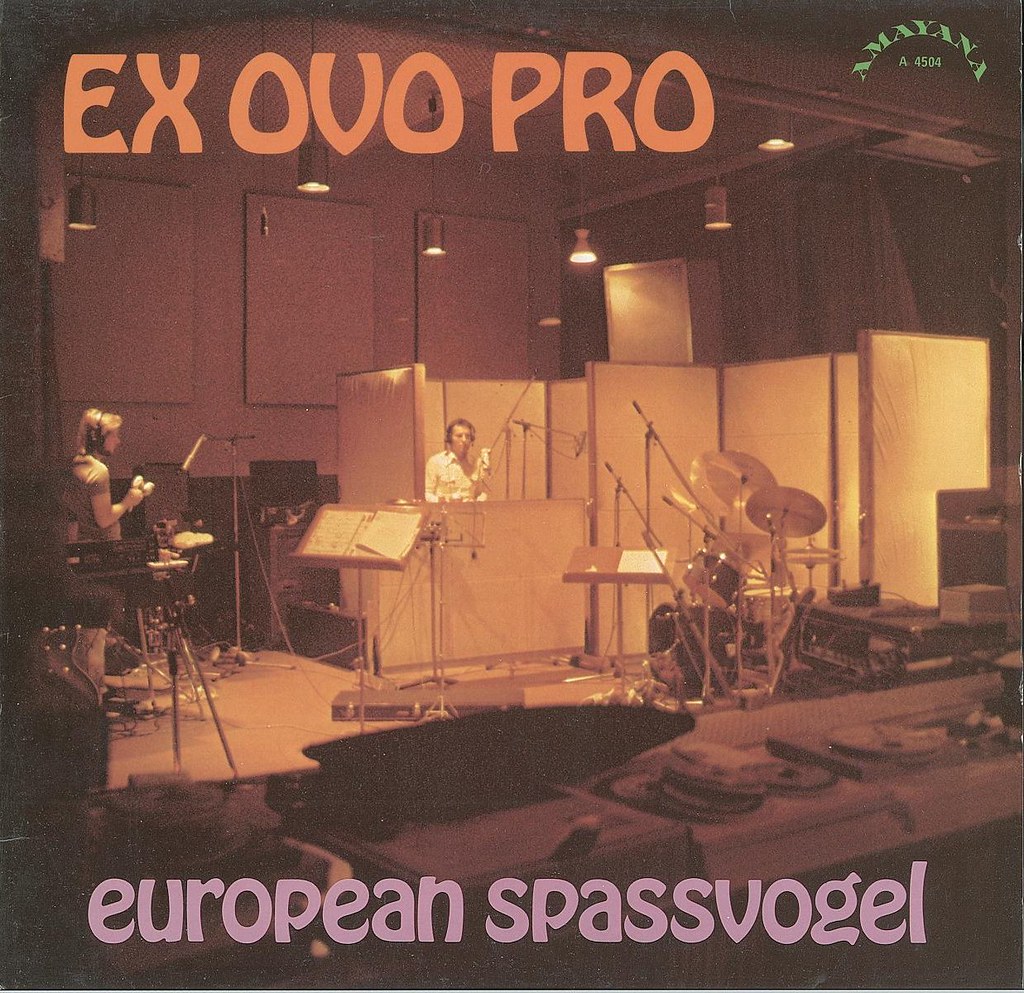

199. Ex Ovo Pro / European Spassvogel (1976)

I don't hear enough of the European jazz scene, past and present, simply because of the music's more limited availability where I live. Thankfully, the web makes the world a little smaller and I was able to locate and hear this out-of-print gem from the Amayana label. European Spassvogel ties a lot of pieces together and after listening to many American groups from the same era, it's refreshing, I really like it. The music is exploratory with anchors in moody vamps and dark melodies. Thankfully, funk is only an ingredient, and the band doesn't dwell on it indefinitely, frequently moving away from it. Wild extemporizations of Mandi Riedelbauch ("In a Locrian Mood") are free and noisy, but the band is really tight. Harald Pompl pounds his traps all around the beat, stuffing the cracks with a unique assortment of percussion and technique. Max Kohler's growly electric bass pours the foundation, and while Pompl does his thing, Kohler keeps time. Hans Kraus-Hubner proviides electric piano, often leading, sometimes coaxing the soloists. It's just a good, chill listen. The songs are concise, and the sides wrap before you can get distracted. If you're like me and get burned out on purely funk-based fusion, this could be what you were looking for.

Labels:

1976,

amayana,

electric guitar,

electric piano,

european spassvogel,

ex ovo pro,

fusion,

germany,

hans kraus hubner,

harald pompl,

jazz,

jazz rock fusion,

mandi riedelbauch,

max kohler,

review,

roland bankel

Friday, November 7, 2014

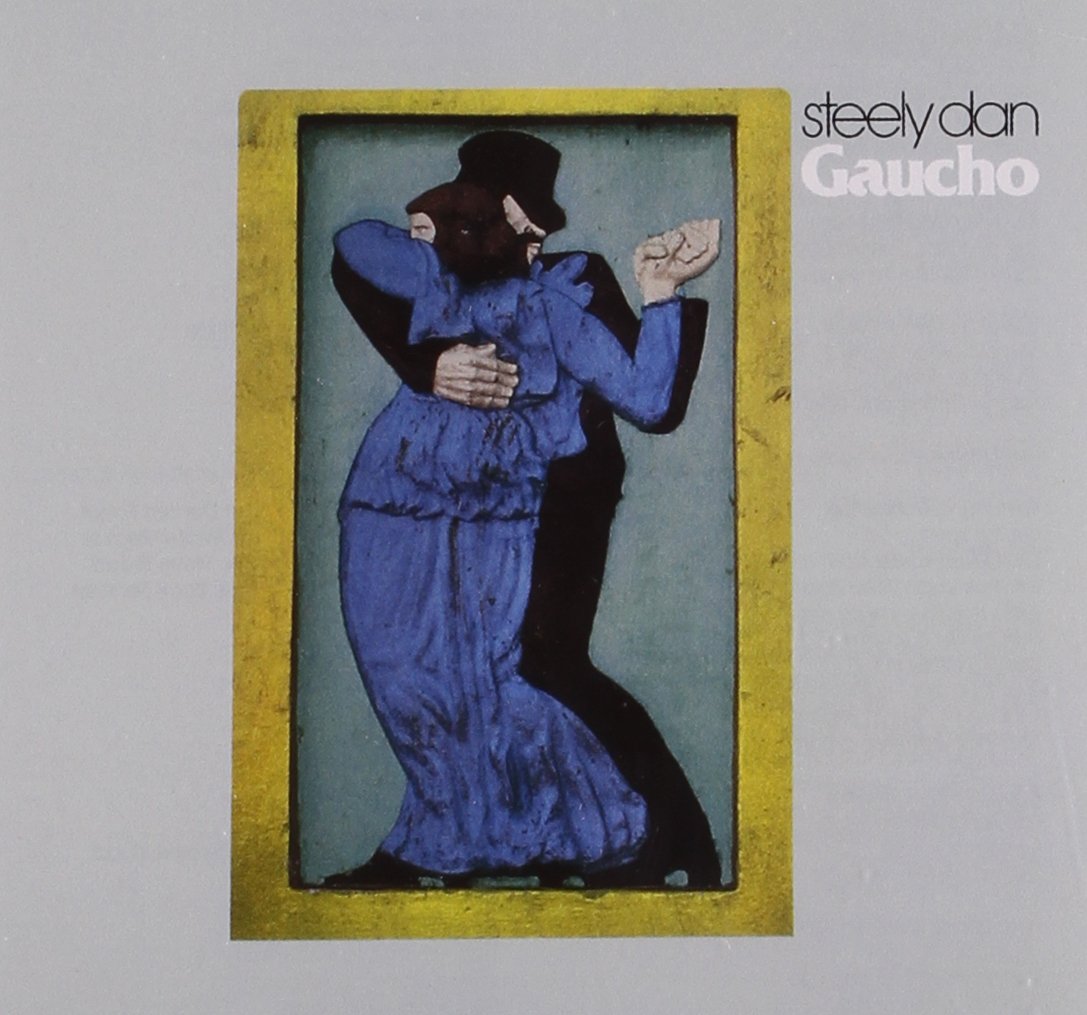

197. Steely Dan / Gaucho (1980)

Gaucho is the last album before the Dan's 12 year hiatus. It's the capstone of the original run, a grooving foil to Aja's majestic sophistication, and the proverbial semibreve rest in the ongoing saga of the Becker/Fagen partnership. Instead of trying to reinvent the wheel, Gaucho swaps Aja's complexity for simple charts and chill vibrations that recall classic rock, rhythm, and soul. Here, the down tempo is on tap and the beats play straight ahead. Hear "Babylon Sisters" shimmer with rich sonority, lush background vocals and immaculately layered overdubs, and you get the picture. Gaucho is also notable for the drum machine (engineer Roger Nichols' "Wendel") lending additional consistency to the already smooth track sequence. If you like Steely Dan, then chances are you won't be disappointed by the fare on Gaucho. But at the same time, while these are unmistakably "Steely" tunes, I think it is also the most stylistically distinct album in the catalog. As always, make of that what you will.

Friday, January 31, 2014

176. Etienne Charles - Creole Soul (2013)

After the uplifting vocal intro by Haitian singer Erol Josué, Charles immediately shows off his chops with "Creole," incorporating some brassy flourishes and familiar licks that recall the brilliance of Lee Morgan or Dizzy Gillespie. And Diz is probably a good touchstone for listeners to whom Charles is new. The music on Creole Soul is just as it sounds, and keeps with the trumpeter's eclectic style that freshly approaches the jazz idiom while remaining warmly reverent of his Trinidadian roots. A greater variety of musics and rhythmical structures -- everything from funk, calypso, bomba, and other musics produced by the Black diaspora -- make Creole Soul something of a departure from his previous albums that were more focused. So the album is like a self portrait. These styles are married with deep sentimentality, sleek musicianship, and mature songcraft in compositions like "The Folks," a Charles original, or spicy, fitting covers like Horace Silver's "Doin' the Thing." With its beguiling spirit and inventive performance, Charles and company negate boxy commercial descriptors like "Worldbeat," or "Latin" at every turn. Tenor sax by Jacques Schwarz-Bart and piano by Kris Bowers add exciting texture and kinetic energy to the already exciting proceedings. Highly recommended!

Labels:

2013,

Alex Wintz,

Ben Williams,

Brian Hogans,

creole soul,

culture shock music,

D'Achee,

Daniel Sadownick,

Erol Josué,

Etienne Charles,

flugelhorn,

fusion,

Jacques Schwarz-Bart,

Kris Bowers,

Obed Calvaire,

trumpet

Thursday, December 26, 2013

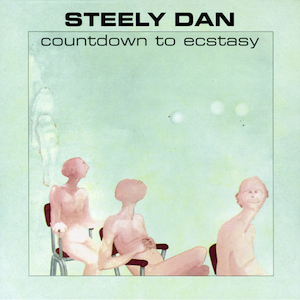

162. Steely Dan / Countdown to Ecstasy (1973)

The followup to Can't Buy a Thrill is like the great early Steely Dan album that no one talks about. It's understandable for a band with things like Aja or Pretzel Logic lurking in the back catalog. Much like Scam, the band's second LP seems destined live in the shadow of its discographical neighbors. But the songcraft is wise and clever, a subtly sophisticated mix of pop, blues, rock, soul and jazz. And like Royal Scam and Katy Lied, it helps set up the stylistic direction that reached its pinnacle with Aja. I find it amazing that this is only their second record. It's an instructional antithesis to the sophomore slump. Appreciating its heights and evenness compared to the debut does much to illustrate the talents of the creators. To say the least, Becker and Fagen are really hitting their stride by this time. The pieces for each future masterwork are in place: First thing to gel is Fagen doing all the lead vocals, killing the herky-jerky transitions heard on Thrill. Denny Dias and Jeff Baxter split the guitar duties, Baxter contributing pedal steel and six string. But there are notable session players, too, like Ray Brown on "Razor Boy," Rick Derringer on "Showbiz Kids," Ernie Watts on "My Old School," and Victor Feldman playing several instruments through both sides. The lyrics come into their own, filled with wry references, quotable one-liners, and unforgettable character studies that are simultaneously explicit and oblique. Some of the music is visionary, too. "Pearl of the Quarter" has been described as "country," but to my ear it is something closer to the further amalgamation of American musical idioms, presaging that which in later decades we would come to call Americana. I love all the SD albums and go through phases where one will sit on my stereo for longer than the others. Right now, Ecstasy is "the one." So excuse me as I put on my headphones and turn on to the curt, sardonic strains of "Bodhisattva" once again....

Saturday, November 23, 2013

153. Miles Davis / Big Fun (1974)

Listening to Miles go electric 40 years ago, critics were in a different position. They took issue with his stylistic developments, because 1974 was much different than 1954. They were too close to see that the intervening years would witness Davis' massive influence on successive generations. Today we see what happened, so we evaluate their merits on another scale. It bears mentioning that these aren't records I can listen to every day. I don't have that kind of time to invest on a daily basis. Like Bitches Brew, the music on Big Fun explores modality through orchestration and arrangement. The tracks are brimming with textures, melodic ideas, and moods. Themes are played and repeated, then recalled, then played again. The effect is haunting, like beasts looming in a fog, vanishing and reappearing. After 22 mnutes, the effect is glacial. Like it says in the liner to Coltrane's Ascension, you shouldn't turn it on without expecting to hear at least a whole side. You can't be interrupted for a few minutes without the magic being broken, and the arc is lost with just a few minutes of play time. Collaborations with Zawinul like "Recollections" or "Great Expectations" fulfill the promise, and typify what's found elsewhere throughout the record. As if you really need a curveball, Davis added sitar and tabla.

Friday, August 30, 2013

128. Rabih Abou-Khalil / Blue Camel (1992)

Like Bukra, 1992's Blue Camel is a stimulating set of jazz fusion with roots in traditional Turkish and Middle Eastern music. Rabih Abou-Khalil's catalog is like a treasure box filled with gems but I think this collection ranks among his best efforts. Instrumentation (alto sax, oud, frame drums, percussion, trumpets, and bass) is similar to the aforementioned Bukra and has similar personnel in Ramesh Shotham. Certainly Charlie Mariano is capable of fusing these disparate musical worlds, and his improvisations with the alto are notable. The album begins with Mariano's tacit, contemplative solo introduction to "Sahara." It sounds like a gently intoned prayer, wafting melodiously through the speakers until Abou-Khalil and the group's other voices join him one by one. Kenny Wheeler on trumpet and flugelhorn is a good choice and his sound adds additional depth to the band. His technique treats the music nicely, like the nimble fingered flair in "Tsarka" and elsewhere. The arrangements develop the compositions with patience, and there is much interplay with the percussionists, which is integral.

Labels:

1992,

alto,

blue camel,

charlie mariano,

flugelhorn,

frame drums,

fusion,

kenny wheeler,

milton cardona,

nabil khaiat,

oud,

quintet,

rabih abou-khalil,

ramesh shotham,

review,

sextet,

steve swallow,

trumpet

Saturday, August 17, 2013

123. Wilton Felder / Forever, Always (1993)

Felder is a hard working session man on the bass and tenor who is deeply reverent of his roots in straight ahead jazz, soul, blues, and R&B. I'm down with that. But on the other hand, this funky, (thanks, Dwight Sills on bass) soul-influenced smooth jazz session is a snoozer. I'm not going to pan it because it's a very slick product with some uncanny melodies and remarkable consistency. Don't take me the wrong way because I like smooth jazz, soul jazz, and fusion. But when I turn on Forever, Always, from the very first note, I find myself looking toward the television for the weather forecast. You feel me? It's one of those records, and a very good one, at that. I find it to be good for the background, good music to listen to if I just want to relax because there aren't many surprises and rhythmically it's all at one depth. Felder's tone is very solid and downright enjoyable, but the music is thin on ideas and while it isn't uninspired, it comes off as routine. Sonically speaking, the mix is creamy and sounds equally at home on speakers or headphones. Did I mention I've retained this album in my iPod? There's a time and a place for everything. So if you're into smooth jazz, 80s soul jazz, or fusion groups without horns, this is the record for you.

Labels:

1993,

dwight sills,

forever always,

funk,

fusion,

nathaniel phillips,

par,

quartet,

review,

rhythm and blues,

rob mullins,

smooth jazz,

soul jazz,

tenor sax,

tenor saxophone,

wilton felder

Saturday, May 25, 2013

106. Frank Zappa / Hot Rats (1969)

Fusion, like the avant-garde, is a thing that everyone approaches from a different angle. Hot Rats is way off the typical fusion track, if you follow the example set by those who left Miles Davis' electric groups. But Frank wasn't moving in those circles. When he made Hot Rats, as ever, he was following his own muse. On the surface, Hot Rats takes the path of a hard rock band, emphasizing the "rock" half of the jazz-rock equation. It is filled out with intricate arrangements played on various reeds, electric guitar, electric violin, percussion, and keyboards. Most of the solos are blues-based guitar workouts or feedback-laden electric violin riffing by Sugarcane Harris (see "Willie the Pimp," "Gumbo Variations"). On the other hand, it also features quirky, composed pieces whose tight arrangements are closer to a synthesis of jazz and classical elements than they are to any mainstream American rock and roll from 1970. Listeners of European experimental music from the same time period, or Rock in Opposition groups like Henry Cow should have no trouble appreciating such pieces. "It Must Be a Camel" and "Peaches En Regalia" are notable in this regard, likewise the horn charts for "Son of Mr. Green Genes," which remained a live staple for years to come. Zappa was also a DIY innovator in the studio. If he didn't have the equipment he wanted, then he invented it, and he was endlessly creative at the mixing desk. So the aurally warm texture of Hot Rats was created with a forest of meticulous overdubs and tape manipulation techniques that Zappa pioneered on his own. Are you new to Frank Zappa? Hot Rats is a good entry point due to its presentation of several characteristics common to many pieces in the FZ oeuvre. It's also very good for rock audiences and toe dippers because it is listenable, contains none of Zappa's lyrics (which range from funny, to off-putting, to complete bullshit, depending on how they strike you), and is also widely available on CD format.

Labels:

1969,

frank zappa,

fusion,

guitar,

hot rats,

ian underwood,

jazz rock fusion,

jean-luc ponty,

john guerin,

max bennett,

paul humphrey,

reprise,

ron selico,

shuggie otis,

sugarcane harris,

violin

Monday, April 8, 2013

75. The Bad Plus / Prog (2007)

I admit the title caught my eye: Prog. I like Bad Plus well enough, even if their brand of jazz-rock fusion tends to wear thin (or thick) on my ears after so long. In jazz we describe them as a piano trio. I say they're a power trio, lying closer to

Cream than Oscar Peterson. Sure, that's a minor conundrum of classification, but this is an interesting album, and what we call "jazz" has become an interesting field, to say the least. There are some terrific originals (I like Iverson's "Mint" and Anderson's epic "Giant"), but this record's trick is in the interpretation of progressive rock like Rush ("Tom Sawyer"), David Bowie ("Life on Mars"), and

Tears for Fears ("Everybody Wants to Rule the World"). These invoke the

roots of both the prog rock and jazz-rock fusion, a crossing of wires in a genre of crossed wires. I love it. Remember Mahavishnu

Orchestra, Miles Davis, and Return to Forever? How they smashed exploratory jazz head-on with the fury of electricified rock and roll? All those

extravagant displays of musicianship that pushed the envelope so far into left field that the genre designation didn't just stop mattering, it ceased to be? My language skirts hyperbole, but that's how I feel when I listen to Prog. I think they've really hit the nail squarely with this record -- it is innovative, attentive, intelligent, and really exciting. It cuts straight to the root of why these compositions have come to be what they are to us, and why we appreciate either style of music, running with that idea until the band is out of string and must make its own. And that thrill is why I listen to jazz.

Wednesday, January 16, 2013

05. Rabih Abou-Khalil / Bukra (1988)

Rabih Abou-Khalil's contributions to the vast world music palette are all so consistently good, yet at the same time, the sound and presiding mood of each one is distinct from the next. I'm always excited to hear one that is new to me. With Bukra, American jazz instrumentation and improvisational technique from Sonny Fortune (alto) melds together with Abou-Khalil's oud in Arabic flavored rhythms and melodies. They are supported by bassist Glen Moore and percussionists Glen Velez and Ramesh Shotham, who chase and tumble like skylarks in pursuit of the rhythm. Moore, a founding member in the Oregon ensemble, is certainly comfortable within this context. But everyone's talents are capitalized: Shotham's interest in jazz and rock, Velez's career proficiency with diverse world musics, and Fortune's jazz background are all harnessed to their full potential. Look out for Fortune's impassioned solo in "Nayla," or his alarming intro to "Kibbeh." Due to the oud's fast decay, in longer passages, Abou-Khalil employs juicy slides and bouts of tremolo picking that produce different textures and affect his choice of phrasing. His pensive and aptly titled "Reflections" closes the album, which always causes me to sit in silence for a few minutes, as if watching the musical caravan vanish in the dark distance.

Labels:

1988,

bukra,

enja,

frame drums,

fusion,

glen moore,

glen velez,

jazz,

kibbeh,

lebanese,

nayla,

oregon,

oud,

rabih abou-khalil,

ramesh shotham,

review,

sonny fortune

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)